“Seek wealth, not money or status. Wealth is having assets that earn while you sleep. Money is how we transfer time and wealth. Status is your place in the social hierarchy. Wealth buys your freedom.”

Naval Ravikant

We live in a society where material objects dictate status, and status equates to power: nice cars, beautiful homes, vintage watches, and flashy bling. The more we accumulate, the more we beat the Joneses, or keep up with them.

The one thing I cannot seem to understand is how people view the exchange of cash for material possessions as a symbol of wealth. As Naval says, 'Wealth is having assets that earn while you sleep.' This statement is so obvious, yet it is completely misunderstood by most people in society.

Wealth is about owning assets that work for you, even when you're not working. It’s about sacrificing today for a more attractive tomorrow. When you invest in assets—whether farms, real estate, or a stake in a business—you’re not just buying something; you’re buying freedom and options for the future.

The difference between consumption and wealth-building boils down to perspective: Are you thinking short-term or long-term? Short-term thinkers focus on what money can buy now—a car, a nice watch, a vacation, or a bigger house. Long-term thinkers, however, understand that while money may be tied up in assets, they understand that cash and a piece of a business are both assets. The key difference is that one is more liquid than the other.

Knowing that you cannot exchange a piece of a business for a watch, or a house, or a vacation is what makes it hard for some to understand how real assets equate to cash in terms of value. The quicker an asset can be converted to something that satisfies immediate gratification, the more valuable it is to a short-term thinker. Humans are inherently short-term in their thinking. However, long-term thinkers recognize that holding a piece of a great business is often more valuable than cash in the bank or a car in the garage. A business generates returns while you sleep, and your net worth is never diminished and can be converted into cash over time.

Cash is merely a token to wealth. It is a medium of exchange that allows anyone to accumulate wealth through long term productive holdings. Even having a small chance of success in a company (i.e. early stage investing) is still net positive compared to exchanging cash for something that eventually depreciates. So long as you use your tokens wisely.

What money buys through possessions is vanity. What money buys through investments is long term freedom and independence. Independence is not as sexy as immediate materialism, and the Joneses will probably disapprove since it is not a status symbol (I would argue that to investors it is - owning great businesses is way sexier than owning fancy cars). But the truth is that freedom lasts forever, while short term pleasures fade.

Here is a table shown in Seth Klarman’s book, Margin of Safety:

This table may seem simple but there is something mind boggling about the law of compounding. As you can see, even low returns on capital can have significant long term benefits, assuming cash is recycled at the same rate.

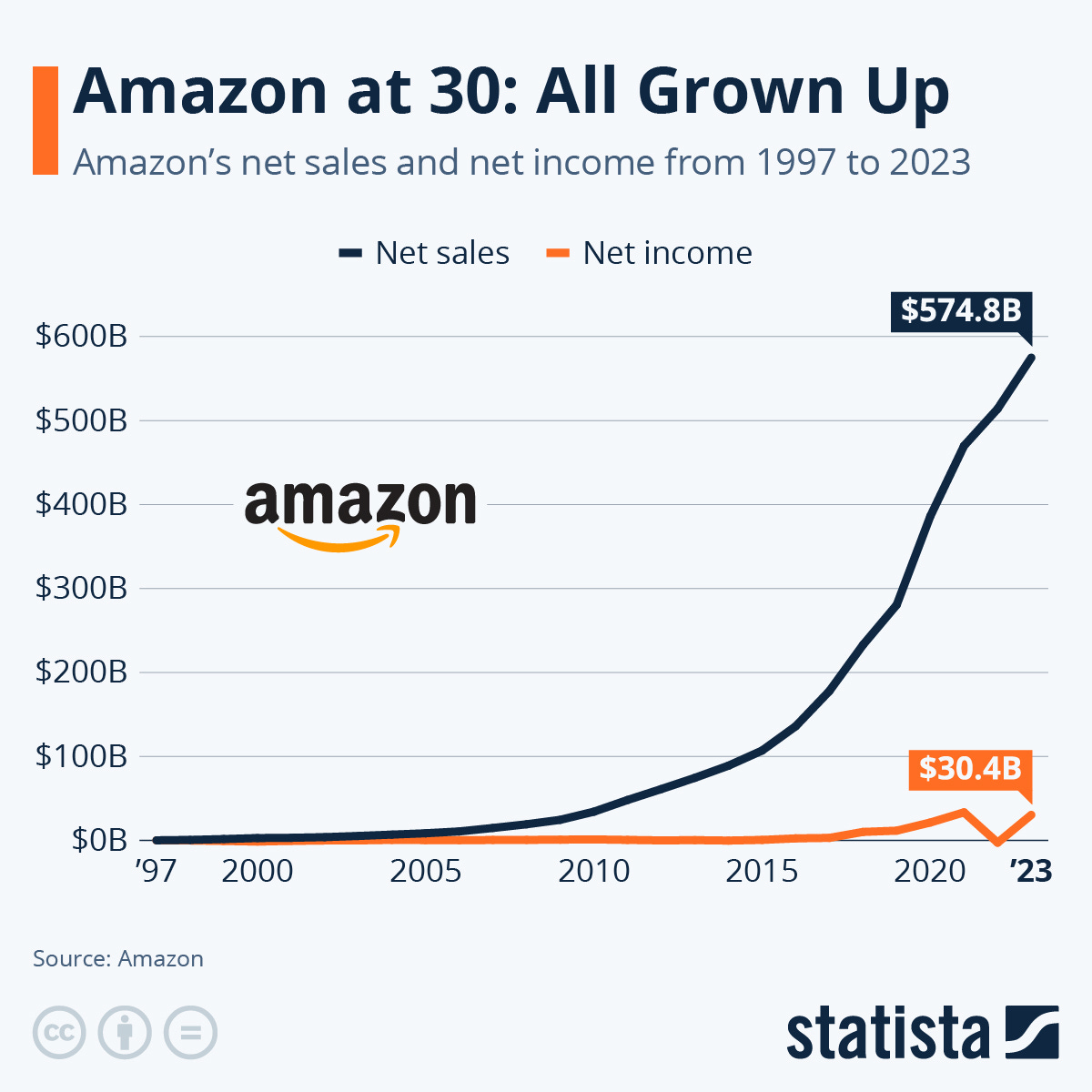

If you leave $1,000 in an account earning 6% per annum and let it sit for 30 years, it grows to $5,743. That’s 5.7 times your initial investment over 30 years. Now, this is where it gets interesting: if you do the same in an account earning 20% per annum, your $1,000 turns into $237,376 in 30 years. Granted, it is difficult to find any asset that can give you a return of 20% per annum for 30 years. But let’s not forget, between 1995 and 2023, Amazon’s revenue grew at a Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 64.5%. Berkshire Hathaway returned a CAGR of 19.68% since 1965. Now you can understand why Buffett and Bezos are so wealthy.

You might say, 'Yeah, but these are exceptional companies.' They sure are, but it is not uncommon for young companies to achieve at least a 20% CAGR over shorter time frames (5 to 10 years). In fact, most young businesses do. If a young company doesn’t achieve at least a 25% return on equity, I would be concerned. I would argue that 25% is the bare minimum for a return threshold on equity (my personal benchmark, though others might see it differently). As you can see, a CAGR of 20% over 10 years turns $1,000 into $6,192—a 6.2x return.

These figures are realistic for young companies during their first 10 to 15 years of growth. Sustaining such growth over 30 years, however, is a different question entirely.

It is no surprise that Bezos decided not to pay dividends. He understood that every dollar paid out meant multiples of that dollar lost in the future. Not only did he avoid paying his shareholders dividends, he also chose to retain a small salary over many years. As of today, Amazon still continues to grow and still does not pay dividends:

From Amazon’s Investor Relations Page

When you hear stories of CEO founders not paying themselves a salary, this is the reason. They are not doing it out of benevolence; they are doing it out of self-interest. Sacrificing a salary allows a founder to keep money within the company enabling it to compound over time, increasing the overall value of the shares. This brings more wealth to the founder and its shareholders.

And what is the purpose of a company?

It is to maximize wealth for shareholders.

Let’s go back to the table:

Why this table is so powerful is that even at lower rates of return, the law of compounding allows anyone to achieve multiples on their money over time—but only if the cash is reinvested. It’s about making money from the money you earn, and then using that money to reinvest again. This is why Einstein once said, 'Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn’t, pays it.”

What does Einstein mean when he says, 'He who doesn’t, pays it'? It means that if you don’t understand this law, it becomes tempting to pull money out of something that could potentially return larger sums later. The irony is that most people fail to grasp the powerful effects of compounding and what it can achieve.

Sure, consistently achieving 20% per annum is tough, but it’s not unusual for companies—especially younger ones—to deliver this year-over-year. Even if you achieve 10% annually, that’s a 17.4x return on your money over 30 years. For example, giving out $1 million in dividends sacrifices $17.4 million in value 30 years from now if your company grows at 10%. Imagine the amounts if rates and starting figures are higher.

The next time you think of selling your shares to purchase something fancy, think twice and consider this law. The opportunity costs become staggering when you start looking at much larger sums of money.

Money is a tool that buys freedom, but you cannot achieve that freedom if you constantly use it for immediate self-gratification. In a world driven by quick profits, rapid exits, the pursuit of unicorns, and the demand for fast cash, the true concept of wealth is being lost. Money has no intrinsic value; it is a token that represents value to facilitate the exchange of goods. This token, which we call money, allows us to buy freedom and independence. The only way to buy more freedom is by increasing the tokens we hold through productive long term assets that generate even more tokens.

Money provides a certain fixed amount of freedom, but money alone cannot make freedom grow. Assets, on the other hand, grow over time, gradually increasing freedom as wealth accumulates. However, this growth requires sacrificing the pleasures of today.

In Warren Buffett’s recent letter about his plans for distributing his wealth, he states:

“Things didn’t look great when I arrived at the beginning of The Great Depression. But the real action from compounding takes place in the final twenty years of a lifetime. By not stepping on any banana peels, I now remain in circulation at 94 with huge sums in savings – call these units of deferred consumption – that can be passed along to others who were given a very short straw at birth.”

This statement might seem unimportant, but it is probably the most most important message in that letter. What he is saying is that he saw the real magic of Berkshire take place in the final twenty years of his life—not because of a change in his investment strategy, but because of the magic that happens after years of compounding. This is why he calls them 'units of deferred consumption.' Call it the good karma of letting the cash compound over time. People forget that he is not wealthy because he holds the cash personally; he is wealthy because of his ownership stake in Berkshire, which does not pay dividends and has a cash position of $325 billion.

In a world obsessed with instant results, compounding reminds us that true wealth is built over time through productive assets, whether in real estate or companies or other investments, as long as the returns justify the risks over time. Wealth is not about chasing fleeting pleasures but about making decisions that serve long-term outcomes. This can only be achieved by understanding that true wealth is not the money you hold, but the assets that earn while you sleep.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company that invests in and builds high-growth, early-stage businesses that serve the underserved Philippine mass market. He is also the Co-Founder of The Independent Investor, a media platform spotlighting early-stage companies and innovation within the Philippine startup ecosystem.