Setting the Vision

Why purpose should drive profit and not the other way around.

In my banking days, I used to overlook the softer side of business, such as branding and culture. In that world, technical 'hard' skills always outshone the 'soft.' Nice offices, spreadsheets, PowerPoint decks, and quick fees ruled the day.

I used to think that everything related to vision—core values, purpose, and mission—was borderline fluff, a way to justify a business’s existence after the fact (making money). The common belief was that finding a product or service that consistently makes money would then compel you to create softer messaging about purpose and mission. However, after years of working in finance, investing, and finally venturing into businesses, I’ve come to realize that having a vision is probably the single most important thing you should establish before even starting a business.

When I speak to people, it’s common to hear them talk about why something will make money, with profit being the main reason for starting a business. Dinner table conversations revolve around ideas that focus on quick money. Of course, money is important—otherwise, why put in the effort to start a business?

But one thing many people overlook are the true pain points in society that are worth solving. When I say 'worth solving,' I mean problems big enough to make a real impact on a large portion of the population.

These insights often comes from within—a personal mission to solve something important to you. When this happens, the focus typically shifts: it’s no longer profit first and pain point second. Instead, at this very early stage, the problem is so personal and important to you that solving it becomes the priority, knowing that if solved it would impact the world in big ways. At this point, profits should be a byproduct of that vision and purpose. This purpose-first approach is also shared by the philosophy of Charles Koch in what he calls “good profit”.

Let’s look at some other examples:

Why did Elon Musk start Tesla?

Because he knew that fossil fuels were a major problem and he saw a world that needed to transition to electric vehicles. He believed this vision was not so far-fetched after all.

Why did Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia start Airbnb?

Because they were frustrated with expensive hotels and the lack of flexible options in the market. They recognized that people had excess space to rent out and saw an opportunity to change the way people traveled.

Why did Sara Blakely create Spanx?

Because there was a lack of comfortable and practical shapewear for women. By addressing a problem she personally experienced, she built a billion-dollar company that improved the daily lives of millions of women.

I could go on and on.

These are some examples of those who faced personal problems that developed into a purpose and a mission. The profits came second. Now it is easy to say “Well what about those other high flying tech companies in Silicon Valley that blow up and exit at a rapid pace. Those guys were thinking short term and focused on the cash payout.”

Not at all. Most of the short-term wins were a byproduct of long-term thinking and a strong sense of purpose and mission. Those founders didn’t expect those exits to happen, and it was never part of their strategy. Those payouts reflect the value placed on the founders' long-term vision. There is a price for everything, especially for long-term future payouts.

Jim Collins, in his book Beyond Entrepreneurship, shares his insights on what he calls the “We’ve Arrived Syndrome”:

“We’ve seen a number of companies encounter difficulty soon after moving into beautiful new buildings and offices. It’s not that the new offices are themselves bad. But they send a signal: “We’ve arrived. We’re successful. We’ve made it” The point is that your company will cross many finish lines in its life, and there will be symbols of these finish lines (a public offering, new buildings, industry awards, or whatever). Your job is to make sure that these symbols lead to continual work towards a compelling mission. When you reach the top of a mountain peak, begin looking for the next one. Set a new mission. If you just sit there, you’ll get cold and die.”

The point he makes is that you should always be looking far ahead and the purpose should almost be unattainable, but should act like a guiding light, with missions that are set far enough that everything else seems insignificant, including material luxuries.

If you look at Jeff Bezos and Amazon today, they preach the “Day One” philosophy through their annual letters. This signifies that they never stop being hungry, despite their size today. They never settle. They reinvest, and set new missions. This is also why they never pay dividends. They always know they have to redeploy into new projects to drive further growth that relate to multiple missions. They know this future growth will reflect in their intrinsic value, and eventually their share price.

Now as an entrepreneur, how do you discover these pain points and develop your own purpose? I would think you would need to be curious and try to reach some truth about the world that others might overlook or not even agree with you on. You can’t just wake up one day and say “I have a pain point and purpose. Let me check with my professor, friends, and family to see if this will work” and then go on to build a company. These pain points are built over time and through personal life experiences after you discover certain gaps in the market that are less obvious to people around you.

As Paul Graham says about knowledge frontiers:

“Once you've found something you're excessively interested in, the next step is to learn enough about it to get you to one of the frontiers of knowledge. Knowledge expands fractally, and from a distance its edges look smooth, but once you learn enough to get close to one, they turn out to be full of gaps.

The next step is to notice them. This takes some skill, because your brain wants to ignore such gaps in order to make a simpler model of the world. Many discoveries have come from asking questions about things that everyone else took for granted.”

Now, if pain points and knowledge frontiers relate to purpose, then you have to be in an environment that throws many of these pain points at you, and you are less likely to find them in more developed markets. Sure, everyone wants to be in New York, Singapore, Silicon Valley, Austin, London, Hong Kong, etc. etc. The theory goes: being in these cities provides you with a sense of accomplishment and purpose. But then you ask yourself, what am I truly passionate about solving?

Competition in this world is fierce and we all know that. We all try to be number one. But the odds are that you will never be number one in the world at any category. And chasing that is just a fool’s errand. As Naval Ravikant says “You’re not going to be number one in the world at any single thing, but you can become the best at the intersection of two or three things.” He is right, and sometimes those intersections are so unique that it gives you a personal moat.

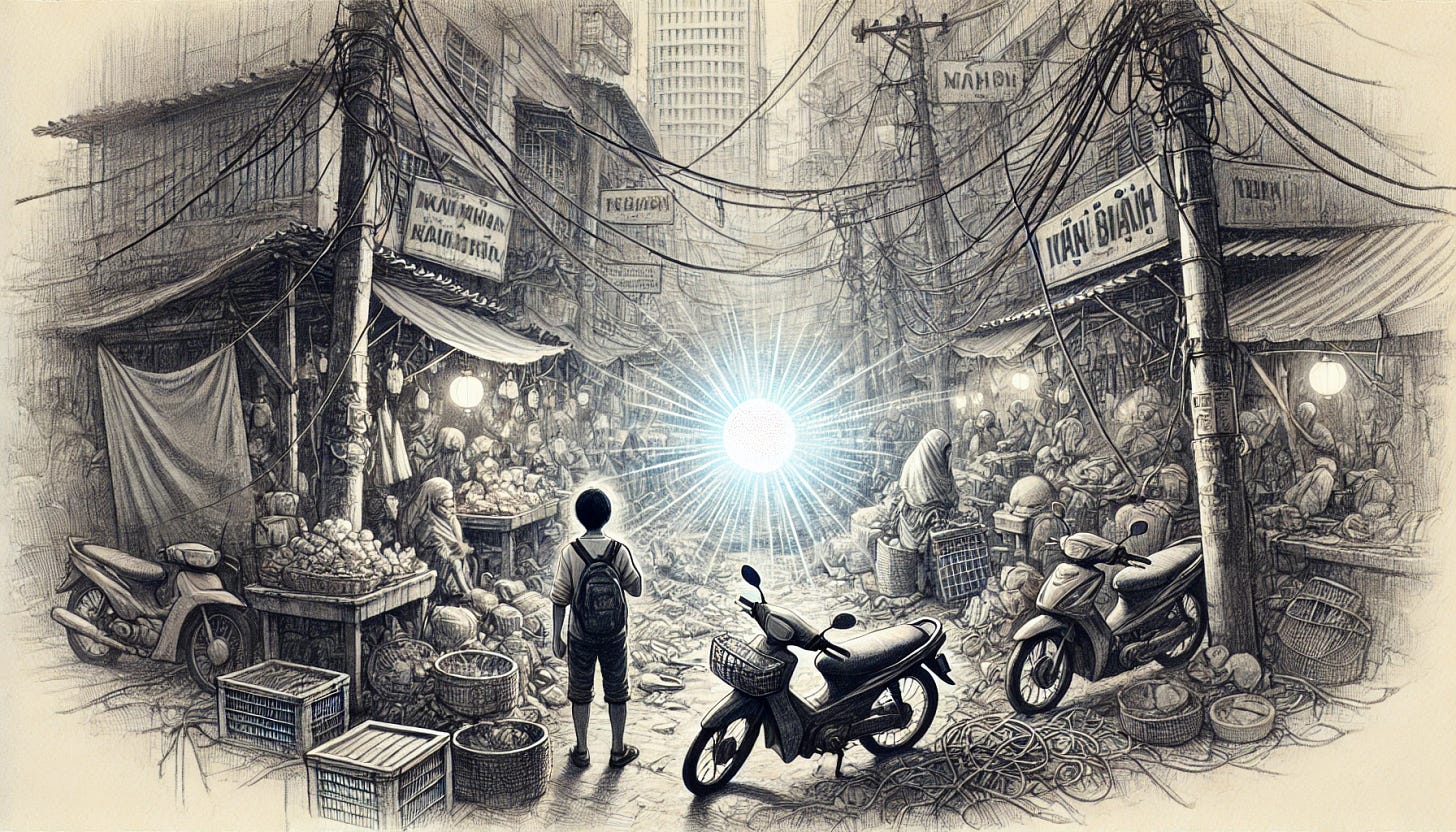

This is why I prefer emerging markets over more developed ones. Emerging markets like those in Southeast Asia present investors and entrepreneurs with large markets that are broken, with more room to create value. The chances of reaching the “frontier of knowledge” are a lot easier and gaps are more obvious. Sure the markets might not be as beautiful as those in Europe and the US, but as the saying goes “where there’s muck, there is brass.”

As of 2023, the GDP of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states was $3.7 trillion. According to the ADB, ASEAN grew by 4.1% in 2023 and is expected to hit 4.6% and 4.7% in 2024 and 2025 respectively.

Compare this to the U.S., which is expected to grow by 2.7%, and Europe by 1.3% in 2025.

I don’t care what anyone says, Southeast Asia is the place to be.

The next time you’re thinking about the next big idea, start by asking yourself: Are you in the right environment to realize your vision? Vision and purpose are not derived from chasing the obvious or playing it safe in beautiful offices in beautiful countries where things are set for you. It comes from noticing pain points that others overlook in areas that are less glamorous. This usually happens in markets that are less visible and still developing, where there is less competition and where things are not as obvious.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company that invests in and builds high-growth, early-stage businesses that serve the underserved Philippine mass market. He is also the Co-Founder of The Independent Investor, a media platform spotlighting early-stage companies and innovation within the Philippine startup ecosystem.