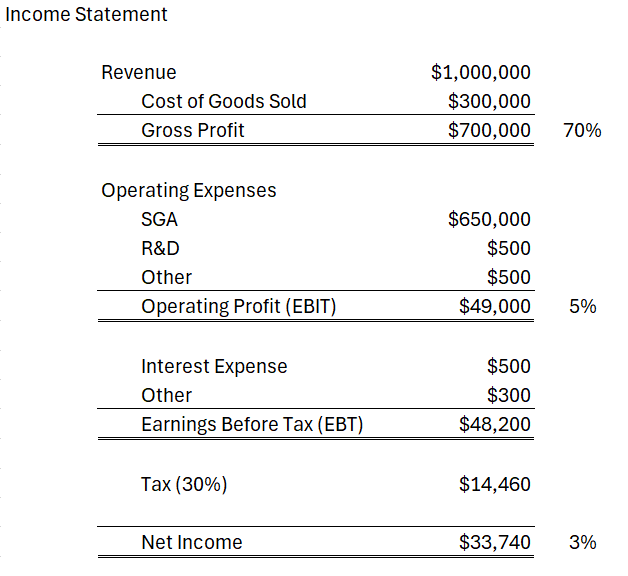

Warren Buffett has a rule for gross margins: stick to companies with gross margins higher than 40%. This is understandable, as higher gross margins signal that a company has a competitive advantage, enabling it to consistently price its products higher. It also allows business owners to properly budget for future outcomes and provides a buffer over operating expenses. However, are all companies with high gross margins equal? Are there exceptions to this fixed rule where a higher gross margin is always better?

Above, you'll notice attractive gross margins (700k/1,000,000 = 70%). However, their significant spending on SGA results in a thin net income margin of only 3%. Overall, their gross margins seem healthy, with strong unit economics but with very little left after operating expenses and taxes. In this case, one would need to examine their SG&A spending and cash management.

Now let’s compare to the following:

In the example above, gross profit margins are only 25% (compared to 70% in the first example). Despite spending the same amount on SG&A, R&D, and other expenses, this company generates 10x the revenue with a healthier net income margin of 13%. This indicates better operating leverage compared to the first example. High operating leverage and strong cash flows are desirable qualities in a company.

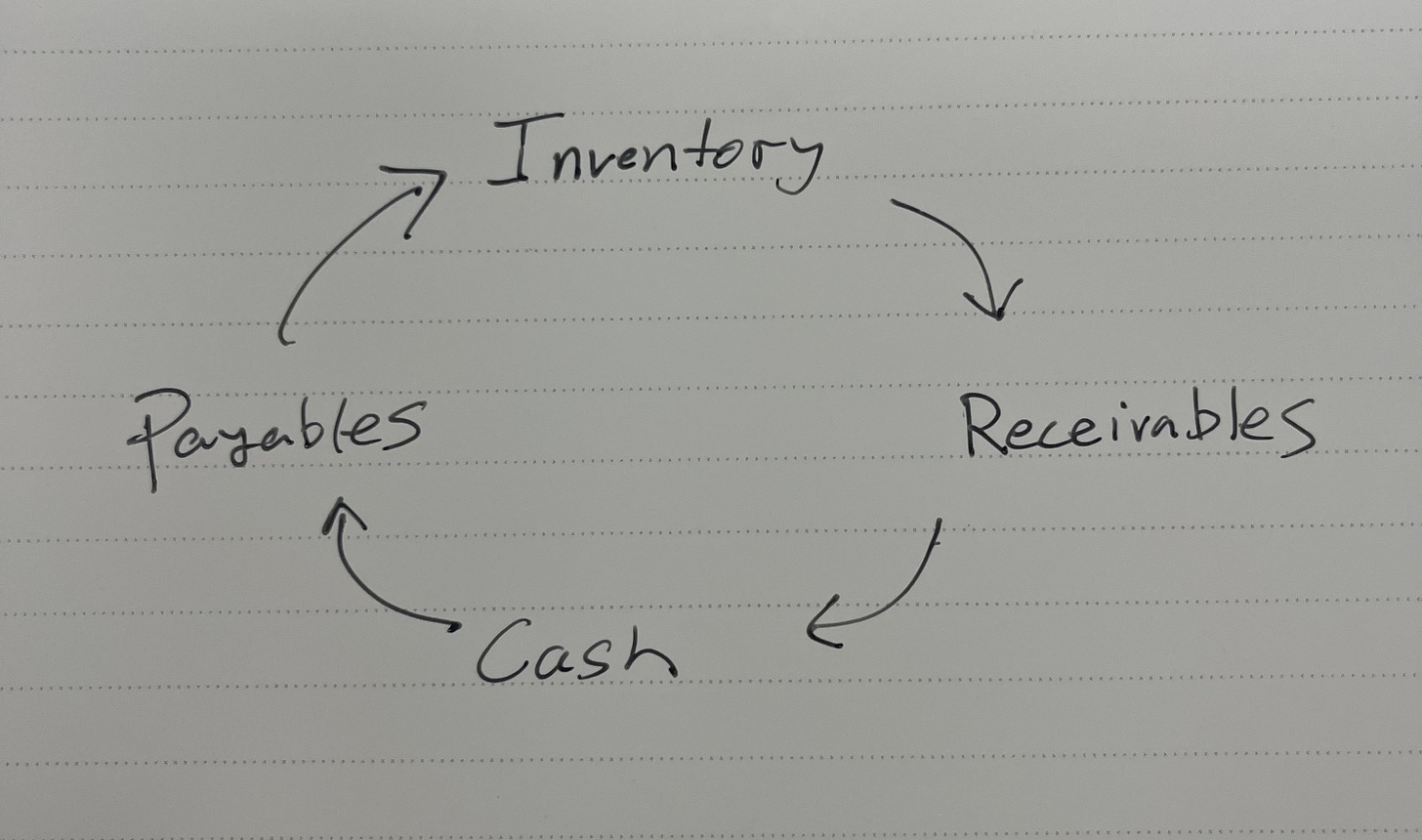

It is one thing to have attractive unit economics, but another to have strong and consistent cash flows. I would prefer a company that generates cash regularly with thin margins over one with high margins but with lower cash velocity. This is why I believe that relying solely on gross margins can be misleading. Understanding the entire cash cycle is essential for gaining a better understanding of a business's health. Ultimately, investors and entrepreneurs are concerned with how their products contribute to total returns for their business. There is a powerful metric that allows anyone to assess this: it is called the Cash Conversion Cycle.

The Cash Conversion Cycle, in a nutshell, is a metric that measures, in days, how long it takes a company to convert its inventory into cash by selling its product or providing its service. It is broken down as follows:

Cash Conversion Cycle = Days Inventory Outstanding + Days Sales Outstanding - Days Payable Outstanding

Let’s break it down in simpler terms since the finance folks like to make things sound complicated. In other words:

The average time your inventory stays in your warehouse

Plus (+)

The average time it takes for you to collect from your customers from a sale

Minus (-)

How long on average it takes to pay your suppliers back (this includes debt)

Equals (=)

How long you convert the product or service that you sell into cash

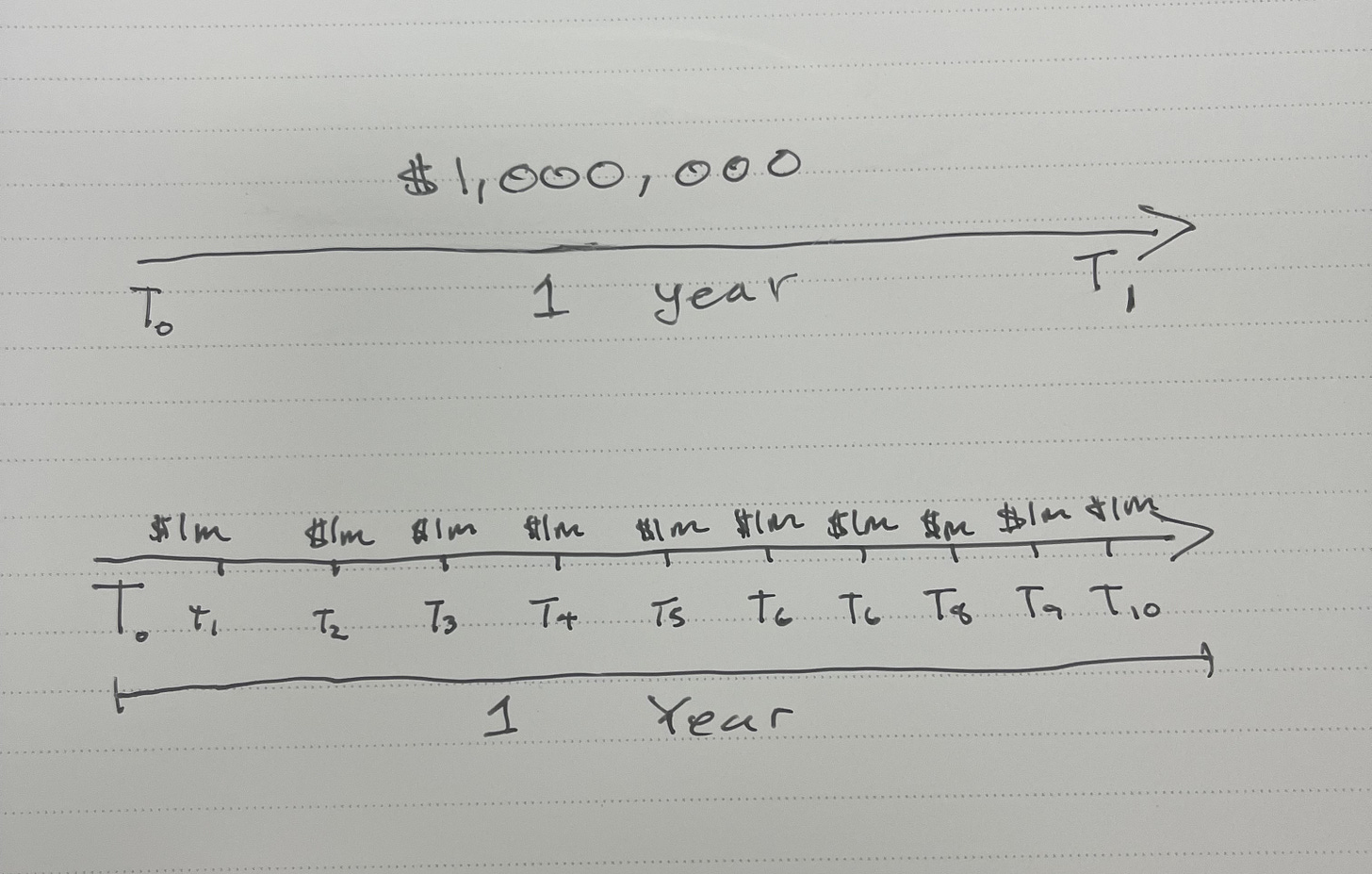

You want to be part of a business that converts your products or services into cash quickly so that you can then reinvest that cash towards future sales and generate more cash. The faster the conversion, the higher the annualized return on your product. In other words, it measures the liquidity of your inventory and will give you a sense of your product returns over a given year. It's very different selling a car once a year versus selling it 100 times a year.

This is why unit economics, and in particular gross margins, do not tell the whole story. There are businesses with amazing unit economics, but their products or services move slowly. Examples of this include high-end retailers with slow-moving inventory, manufacturing companies with slow production cycles and extended receivables cycles, services where collections can be an issue (such as catering), or businesses in general with inefficient receivables management and high debt (resulting in interest payments).

On the other hand, there are businesses that operate with thin gross margins, but move products quickly. Businesses that fit this profile include subscription-based businesses, FMCG (Fast-Moving Consumer Goods) companies, companies with efficient production processes, and trading companies that can extend supplier terms but collect efficiently and turn their sales over quickly.

The key here is to sell a product that addresses a large market, potentially becoming widely popular without being entirely commoditized. If this can be achieved, then you have a winning product. I say “not entirely” since winning in a market doesn't always require a perfectly differentiated product; it can also be achieved through efficiency, superior customer service, cost advantages, and a strong distribution moat. You might still have low gross margins, but dominating an industry despite this isn't necessarily a bad thing. This is exactly what Amazon did. They provided many products that already existed but made them more affordable and convenient for the end consumer, eventually capturing higher gross margins in later years.

Amazon Gross Margins

I am not saying that we all have to be like Jeff Bezos, but we all can identify inefficiencies in the way products and services are delivered to the end customer. Studies show that customer service alone can have a significant impact on your sales.

This is why I like trading companies, where gross margins are thin but operating expenses are low, and cash conversion cycles are short. Sometimes they can even be negative (known as back-to-back trades). Consistent cash flows throughout the year suggest high-quality sales that meet regular customer demand.

Next time someone flashes a slide about their strong unit economics and healthy gross margins, dive a little deeper. Ask how they're making money and have them walk you through the cash conversion cycle. Many skip this step, but those who do get a clearer view of their business and have better chances of success in the future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company based in the Philippines that partners with entrepreneurs across a wide range of industries. He is the Co-Founder and Director of The Independent Investor.