On the Brink of Something

Finding your next breakthrough should be easier than initially thought.

In my college years, I used to think starting a business was nearly impossible. Why? I thought most things in life were already taken, and if they weren’t, you had to have something special to attain them, such as a new invention or a truly unique service that nobody else has thought about. What I learned after 13 years of working in the corporate world is that this is not true at all, and starting a business should be easier than conventional wisdom suggests.

“Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact: Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you and you can change it”

- Steve Jobs

I remember taking an entrepreneurship class in college and thinking about how hard it would be to prepare an idea and pitch to the class. Our group’s idea was to create a platform that would allow athletes to network and bridge them with jobs as a backup in case they failed to reach their athletic dreams. Long story short, the idea never took off, and our group didn’t come close to getting an A. I remember how awkward it felt being told how to prepare the pitch; it just felt unnatural. This forever shattered my dream of entrepreneurship and further pushed me into believing that entrepreneurship was reserved for the truly gifted, and maybe even those in Ivy Leagues. In fact, I believed that only schools held authority over one’s direction after college.

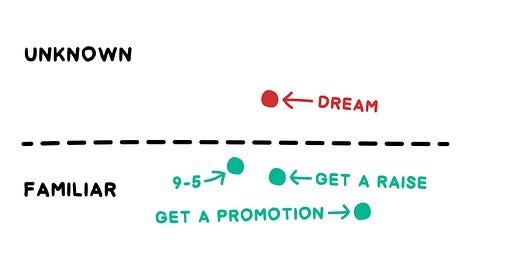

Note: Picture drawn by Janis Ozolins

We are familiar with what has been done, and having an entire establishment supporting you along this familiar path imparts a sense of ease and security.

I eventually entered a career in Finance and concluded it after spending 7 years in Investment Banking. It took me almost 13 years to figure out that it was time to move on. When I did, I started investing in early-stage companies. My first year as an investor gave me knowledge about the early-stage world and what it means to start and grow a business without actually starting one myself. The beauty of early-stage investing is that it gives you a front-row seat to the building blocks of a business, and there is no better way to learn than by having skin in the game. Studying a case study and/or taking a class is very different from having your own money tied to a company. When your personal savings are exposed, you will do whatever it takes to try and succeed, and that adds to the experience. A seasoned investor once told me that the only real way to learn how to invest is to invest your own money, and I couldn’t agree more. I never looked back after that.

This investing experience brought unique knowledge that was completely new to our investors, so much so that it brought many questions with few answers. The only way to find out was to ask other like-minded investors if they were experiencing the same challenges. Over time, we started learning about the common denominators that made companies tick and what the value drivers are of the most successful companies. This new knowledge brings more comfort to the idea of starting your own business. Once you begin learning the value drivers of successful businesses (from being an investor), you start becoming curious with your own ideas and are more willing to test them. This then becomes the bridge between investing and entrepreneurship.

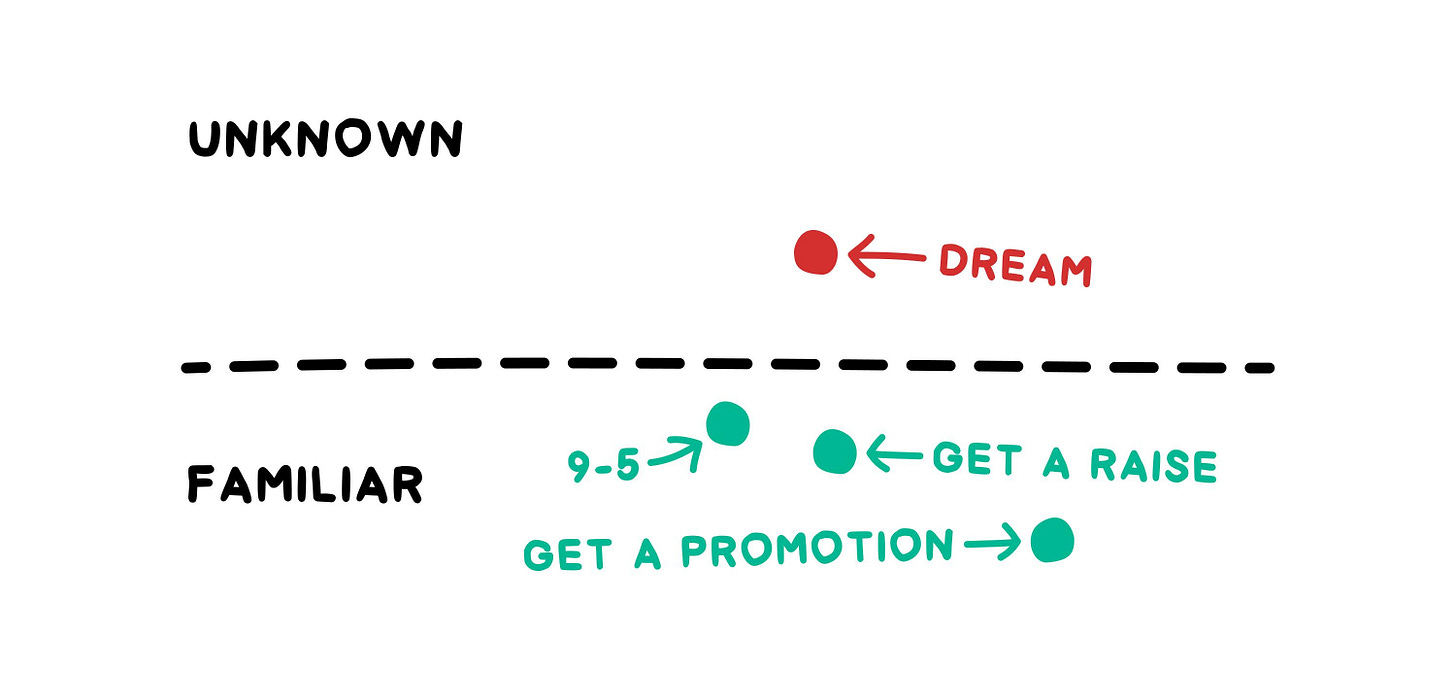

In Janis Ozolin’s recent newsletter, he breaks down how learning helped him achieve his dream, and he did this through constant reading and learning. He further illustrates his point below.

Note: Picture drawn by Janis Ozolins

Everyone learns differently, but the point of this is that the only way to become comfortable taking risks is by fostering curiosity and gaining new insights through experience. I will expand on Ozolins’ point by adding two more factors:

(1) Be curious and stay in perpetual learning mode. Read books. Reach the brink of the subject matter, and be knowledgeable enough to be dangerous, but not a subject matter expert. If you are curious about this approach, I highly recommend Paul Graham’s essay on this subject: https://paulgraham.com/greatwork.html.

and

(2) Tinker with projects that have a low downside. This allows a person with incomplete knowledge, who might otherwise believe in a product or service, to tinker and test them in a market at a relatively low cost. As Joel Greenblatt says, “Look down, not up.”

For point (2), how do you limit your downside? While it may sound counterintuitive, the approach here is to prioritize assessing the worst-case scenario in all situations. You ask yourself, “What could possibly go wrong, and if it does go wrong, what will my returns be?”.

“One way to create an attractive risk/reward situation is to limit downside risk severely by investing in situations that have a large margin of safety. The upside, while still difficult to quantify, will usually take care of itself. In other words, look down, not up, when making your initial investment decision. If you don’t lose money, most of the remaining alternatives are good ones. While this basic concept is simple enough, it would be very difficult to devise a complicated mathematical formula to illustrate the point. Then again, not much downside to that . . . “

- Joel Greenblatt

If you review the two points above, you will realize that point (1) is probably done by a small minority. Most people don’t read despite the fact that it brings huge benefits, and how readily available books are for everyone. As for (2), only a very few engage in it. Why? Most will continue improving upon their own position in their respective companies instead of striking new paths. This may be the reason why entrepreneurship is so rare. In addition, most companies go against tinkering. They prefer grand plans over experimentation, which can delay execution. Not to mention board approvals and layers of bureaucracy.

So how do you tinker?

When we look at opportunities, the sequence of questions will look like the following:

Is the industry attractive with strong unit economics? Meaning, is it a big market and do most companies in that particular industry make money?

If yes, proceed to the next:

Are there major inefficiencies in this industry? Meaning, is there room for arbitrage (are things broken) ?

If yes, proceed to the next:

Is there a large upside relative to downside? Meaning, are the returns attractive relative to its downside risk? If so, does it meet your minimum downside threshold?

Note: I will have to digress here to discuss what it means to have an attractive return. Let’s say you had a magical machine in your garage that spat out $100,000 every month for 5 years. Nothing more, nothing less. It spits out this amount, tax free, and straight into your pocket on the 5th of every month. How much would you offer for that machine assuming it was a blind bid? When I ask people this question, they all give different answers. Why? Well, this might seem equivalent to a risk free bond, but then you might ask about the house in which the machine is in, the condition of the machine, risk of theft in the neighborhood, fire risk, country risk, and other factors that you might not have any information on. Even if it is a safe village, the amount will differ. Some will want 15% on their money, some 20%, some 10%. If you ask the same question, but then say that every 2 years, there is this machine thief who lurks the neighborhood and steals 1 out of 10 magical machines. How much would you then pay for the machine today?

I will not go into probabilities here but the point is that entrepreneurship is the same way. We all are looking for that magical machine that spits out money, but the future of most machines is uncertain, and thus each of our return thresholds are subjective and based on our risk preferences.

Going back to 3, if the answer is yes, proceed to the next:

Is it worth my time to look a little deeper to find out (move closer to the edge of knowledge, but not an expert)?

Note: If the learning curve is tough and impossible for you to get close to the frontier, then pass. If achievable (with little downside in terms of time), then proceed to the next:

Are you able to start the business with a small amount of capital?

If yes, proceed to next:

Do you have a network of people who you trust who are better than you in this field? If so, are they willing to partner with you to tinker with small projects?

If yes, proceed to initial testing and keep your eye on cash.

This is by no means a sure fire way to succeed in entrepreneurship and I would not consider myself an expert, but this has worked for me. All my companies are early stage and have yet to blossom, but I have taken the plunge and will continue to tinker.

This approach is about having a value lens to entrepreneurship and is taken from the value investing playbook by the likes of Warren Buffett, Joel Greenblatt, Seth Klarman and others. Investing and entrepreneurship are very similar in the sense that you have to study the downsides at all times, and constantly balance the risk/rewards as you seek new opportunities. It’s not just about focusing on risk/reward. It’s also about knowing your network, whether you have the right resources to make it happen, and being open to partnerships as they see fit. This is what differentiates an entrepreneur from an investor.

The next time someone laughs at your idea or rejects your funding request, just remember what Warren Buffett said: “You're neither right nor wrong because other people agree with you. You're right because your facts are right and your reasoning is right - that's the only thing that makes you right. And if your facts and reasoning are right, you don't have to worry about anybody else.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company based in the Philippines that partners with entrepreneurs across a wide range of industries. He is the Co-Founder and Director of The Independent Investor.