In the beginning of a startup journey, there is a moment between idea and execution. The key is finding the glue that bridges the two. Everyone has their own glue that makes ideas and implementations stick, which then gives them the confidence to build out their first business.

Someone once said that a startup fails because either (1) the founder gives up or (2) the company runs out of cash. I forgot who said this, but it still rings in my head when we spend time with early-stage companies. I have found that having the right co-founders and core team in the early stages is one of the most important factors in bridging an idea to execution. That said, I have seen founders try to go out and do things themselves, and it has worked for some.

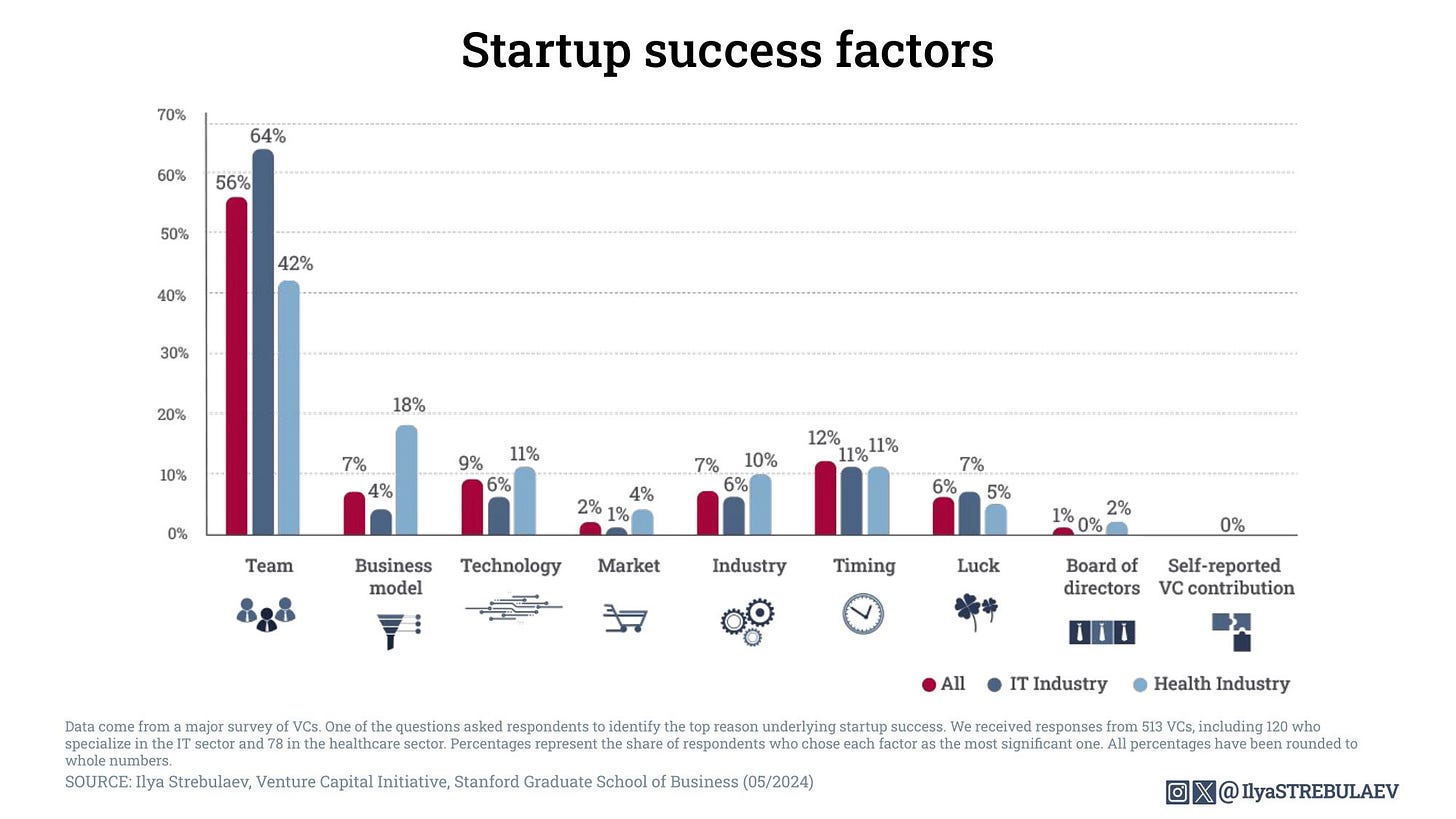

Both options have worked for startups, but studies show that having strong team dynamics is one of the most important factors in the success of any company (see below for survey results). Some founders are good at creating their own management teams that are detached from ownership, while others prioritize shared equity early on to ensure all incentives are aligned before a product is kicked off. I prefer the latter model, as human incentives tend to be the most powerful drivers of performance.

Those who prefer the solo approach often come back with the question, 'But what if one of the co-founders leaves and the founding team becomes dysfunctional?' There are many 'what ifs' in the early stage, and I don’t have an answer. Building a team is personal and requires an element of trust with expertise, and this is where it becomes more of an art than a science. Combining the two can work wonders for any founding team. If one is lacking, the future outcome becomes more uncertain. Similar to good bands, many dissolve due to conflict, while the best maintain close contact and flourish for the rest of their lives.

Ilya Strebulaev, who is the founder of the Venture Capital Initiative at Stanford University, shared the following statistics based on surveys involving over 500 venture capitalists, focusing on the primary factors behind successful startups. Below were the results:

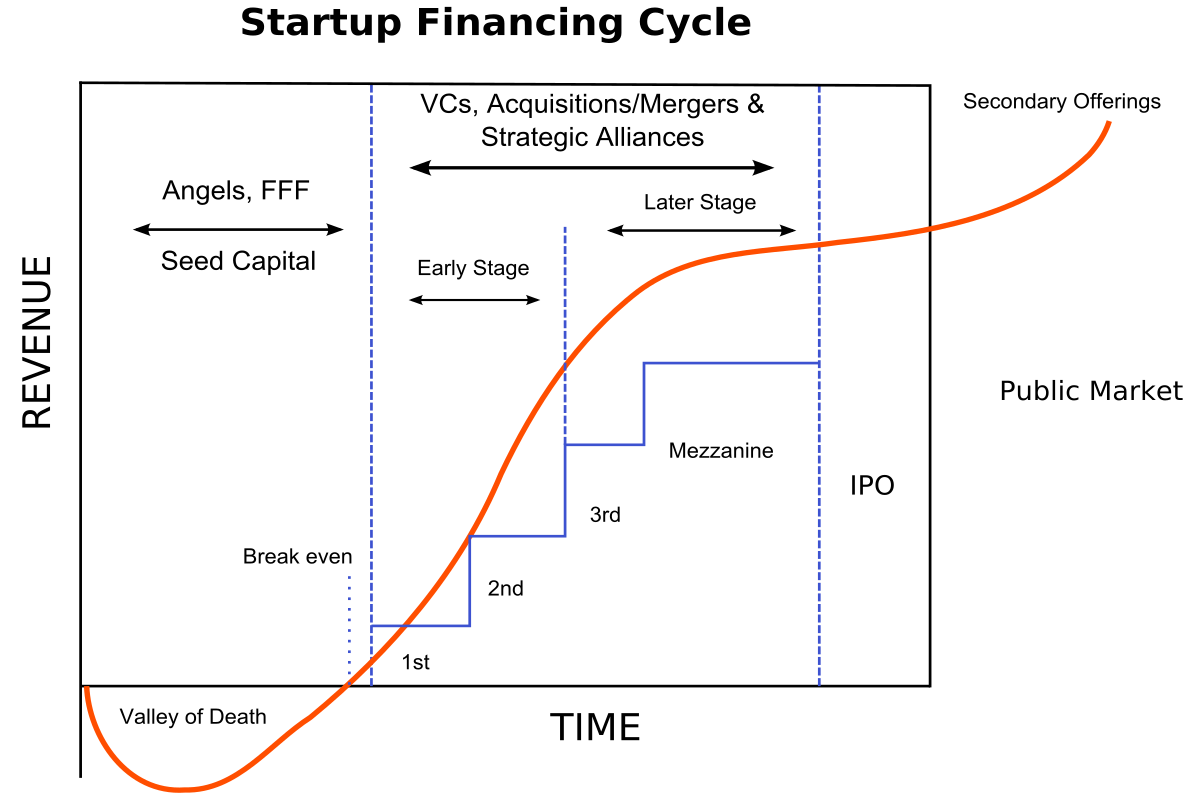

If you notice above, the company’s business model doesn’t make a dent in the success of startups in the eyes of most investors. Why? Because everyone has ideas, and very few know how to execute them. A big part of execution is having the right core team that is capable of crossing the Valley of Death.

Picture source: Wikipedia

What happens in the Valley of Death?

According to Investopedia, “A startup company's death valley curve is the span of time from the moment it receives its initial capital contribution until it finally begins generating revenue. During this window, it can be difficult for firms to raise additional financing since their business model has not yet been proven. As its name implies, the death valley curve is a challenging period for startup companies marked by a heightened risk of failure. During this period, the company depletes the initial equity capital provided by its shareholders.”

This is the stage right after an idea is born.

A team is formed, and the key infrastructure for future success (or failure) is built. Many startups don’t pass this stage, and the most important line in the previous explanation is that 'the company depletes the initial equity capital provided by its shareholders.' This means that whatever investors put in is expected to be fully used to build out the initial stage. Once it is used, it is either they make it, or they don’t. If they don’t, they need a good explanation to investors to convince them to 'top up' and keep going. If they do, they should see some trendline and momentum, which gives them a good chance to either grow organically or pursue another funding round.

The funds usually go toward marketing, finance, sales, product build-out, etc. It can be the most stressful period of the entire company lifecycle (since it has the highest risk), and a founder will need as much support as possible. This is where the team comes in.

As I mentioned in a previous article, black swan events are inevitable, and one has to have the resilience to face them. On top of that, as a founder, you are probably doing this alone with a lack of support from family and friends (most startups are ignored by people around you as you are building—that is the nature of being contrarian). What I have found to be very useful at this stage, beyond the co-founding team, is a strong network of professionals who can assist you with advice, whether they be lawyers, accountants, contractors, designers, brand managers, social media experts, investment bankers, lenders, and more.

Side note: If you are stuck in a 9-5 job today and dream of one day starting your own company, I recommend building your network with people who have different skill sets, even if those skills are outside your domain. It will pay off later when you need support. There were many instances in our journey where we reached out to people we worked with years before and did not expect to need their help, but we did. Everyone around you has something special to offer. Building those foundations early will pay off in the long run.

The job of a co-founding team is to be good conductors, and conductors have to have a feel for the musicians and their skill sets with each instrument. It helps when the conductors were once violinists or pianists. Building a good co-founding team is like getting the right conductors who have experienced specific instruments and now work together to create something special.

Picture source: ClassicFM

So the type of mindset needed for either path is obvious, but I will provide two examples to show the two paths:

Path 1

A solo founder has an insight.

The solo founder builds a product and approaches a target market.

The solo founder starts marketing the product.

As the company gains decent demand for the product, the solo founder starts hiring people underneath to mitigate risk.

The team grows larger, costs rise, and management shareholder responsibilities increase.

The founder, feeling alone, realizes the need for advice but understands that extra advice comes with a cost or requires hiring talent.

His stress levels go up knowing that he is all alone in this journey and can’t bounce ideas off others. He can reach out to his hired COO but it’s a Sunday morning and will probably have to wait until 8am the following morning to check on something.

The founder fills in any gaps as they scale the business, seeking the right professionals to guide them, while sacrificing pay and family time.

Path 2

A founder has an insight.

Realizing he can’t do it alone, as he excels only in branding, the founder acknowledges potential obstacles that require expertise in areas such as finance, fundraising, accounting, operations, IT, etc.

The founder seeks a co-founder and eventually finds one good at operations.

Both co-founders assess the opportunity and see further roadblocks and complexities along the way, and decide to look for another co-founder, and they find one good at logistics.

All three co-founders experiment and test the market, recognizing a missing key skill necessary to navigate challenges. They find one more co-founder who is good in IT and cybersecurity to further mitigate risks.

All four co-founders realize that they have the team in place to start testing and bridging their product to the market.

The co-founders create a lean core team that believes in the mission and vision, and executes the plan.

While stress levels are high, a shared sense of purpose prevails among the co-founders, with capital allocated for a leaner team.

I understand that giving up equity is costly, but I don’t believe it’s as costly as increasing the risk of failure during the Valley of Death. Being generous with equity as a solo founder helps mitigate that risk. The potential upside at the early stage of any business is substantial, and significant wealth can still be generated despite this dilution. This is why I like the latter approach to ensure that all risks are addressed and the right foundation is laid for future success.

This is also why most large corporate entities have a difficult time incubating companies. For one, incentives are misaligned (they are more aligned with the corporate entity), and once they start considering building a co-founding team, the idea of giving up more equity to mitigate risk seems foreign and doesn’t make sense for larger companies. Yes, they provide added support as a corporation, but that comes with more bureaucracy and layers of approvals, which diminish innovation and creativity. Money can’t buy creativity and culture.

At this stage in their life, startups need to be nimble, and people often forget that determining how the pie is split is one of the most important decisions any founder will have to make when starting their own business.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company based in the Philippines that partners with entrepreneurs across a wide range of industries. He is the Co-Founder and Director of The Independent Investor.