A friend of mine suggested I pick up the 7th edition of Security Analysis by Ben Graham, who is considered the 'father of value investing.' Graham is considered the Bobby Jones, Babe Ruth, or Bill Russell of the investment world. The difference with this edition is that some of the top modern-day investors, including Warren Buffett, Howard Marks, Seth Klarman, James Grant, Roger Lowenstein, and others, updated it to reflect the modern day. This is like Tiger Woods grabbing an old golf manual from Bobby Jones and adjusting it for today’s golf athletes. As an investor and entrepreneur, it would be a mistake to ignore this book.

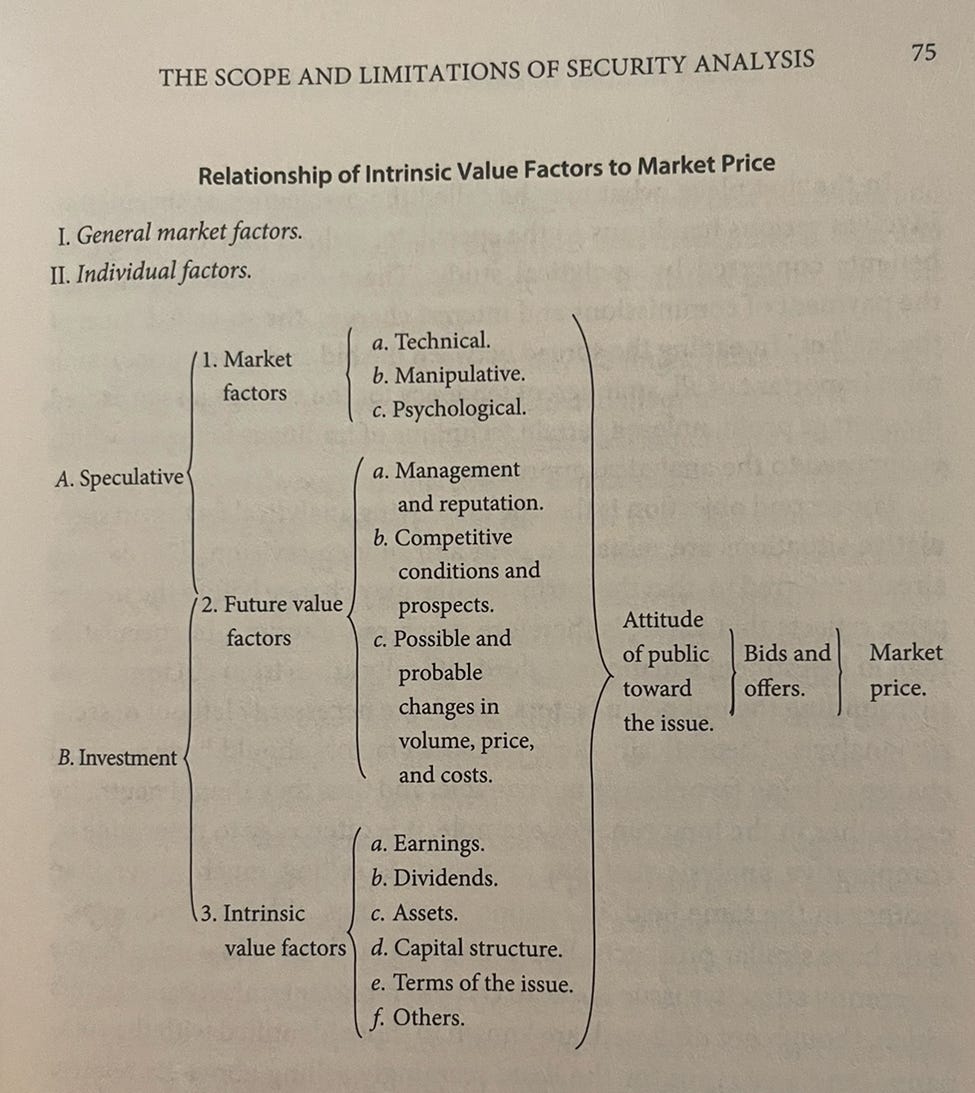

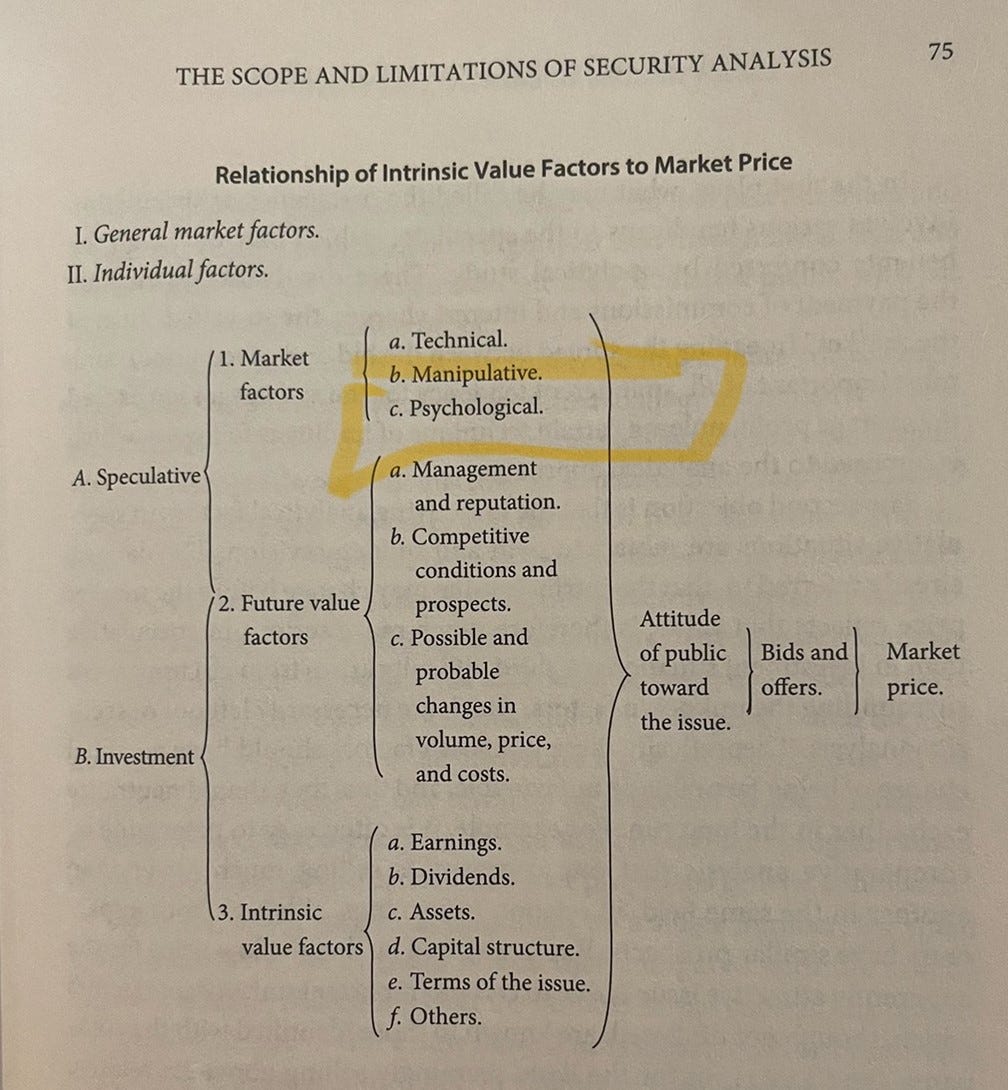

I am still on page 75 of the book (of the 800 total) and there was a specific chart that caught my eye:

It will be evident from the chart that the influence of what we call analytical factors over the market price is both partial and indirect — partial, because it frequently competes with purely speculative factors which influence the price in the opposite direction; and indirect, because it acts through the intermediary of people’s sentiments and decisions.

In other words, the market is not a weighing machine, on which the value of each issue is recorded by an exact and impersonal mechanism, in accordance with its specific qualities. Rather should we say that the market is a voting machine, whereon countless individuals register choices which are the product partly of reason and partly of emotion.

- Ben Graham

We have heard countless commentaries about how Ben Graham’s methods are 'old school' and that he would not survive in today’s world. But the reality is that during his time, pure analytical models generated the biggest outsized returns. Keep in mind that this book was written in 1934 in the middle of the Great Depression (1929 - 1939), and this may be the reason why he was so conservative with his stance on speculation. Many companies were trading below book value, and he discovered the price-value arbitrage and captured it before anyone else had a chance to.

The Great Depression was a nasty period, and stocks sank significantly and for a very long period of time. Ben Graham still believed that value (fundamentals) should eventually catch up to price despite stocks not moving for some time. As more market participants realized that companies were trading for less than book value, they rushed for the gold. Over time, they did go up, and eventually new forms of 'value' emerged.

Today, it would be impossible to find opportunities like this unless a company is going through serious trouble (prices tend to be efficient when it is that obvious).

If you notice in the chart above, Graham considers intrinsic value factors (earnings, dividends, assets, etc.) as investments, while both market and some future value factors are considered speculations.

Basically, what this chart shows is that Graham doesn’t believe that management, brand, competitive landscape, technical trends (momentum), and psychological factors have an effect on the ultimate value of a company, hence it falls under his definition of speculation.

His belief was that value is ultimately based on pure fundamentals (intrinsic factors of the company such as historical earnings and cash flow). You might wonder, how can this be the case? It seems so backward for someone to not even consider the 'softer side' of business when making investment decisions. Well, it all goes back to the concept of time and compounding. In his day and age (and when Warren Buffett started taking Graham’s classes), the few value investors that existed practiced what is called 'Cigar Butt Investing'. These investments were shorter-term but played off the arbitrage between price and intrinsic factors, and they worked well. Price generally moved in tandem with intrinsic factors quickly, but not quick enough for the general market to beat Graham and his team. Graham and his value investing community made a fortune, and soon Warren Buffett followed.

Source: Wallstreet Journal

If we call the Ben Graham days 'Part 1', the next phase (Part 2) happened when Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger picked up a few pieces of his knowledge and applied their own model. Let’s call it the Berkshire Model.

Part 2 - The Berkshire Model

The story of Berkshire Hathaway is an interesting one since it all started with Buffett investing in a failing textile company in 1962 (he was investing through another vehicle with the guidance of Graham well before this point in time) and spent years trying to turn it around.

Source: Omaha World Herald

Today he says it was his worst investment, but he ironically kept the name intact —Berkshire Hathaway. During this time and prior to the purchase of Berkshire, Buffett applied the cigar-butt approach that Graham preached, and it continued to work. He would focus on intrinsic factors, buy cheap companies, and wait for the market to realize their true worth, and then sell. He did this day in and day out and made a killing doing it at a time when markets were still highly inefficient in the short run.

One day in 1959, Buffett met Charlie Munger, and they shared ideas on how to continue their investments well into the future. However, the issue was that Munger had a different investment philosophy than Buffett (there is a long story behind this, and if you are interested Alice Shroeder wrote an excellent book called Snowball). He told Buffett that real money is not made by trading in and out of stocks for small spreads. Real money is made when you 'sit on your ass'. This is when he came up with the famous line that changed Warren Buffett’s life.

“A great business at a fair price is superior to a fair business at a great price”

- Charlie Munger

For Warren, this sounded unusual. How can someone pay a high price for all these other 'soft factors' such as management, branding, competition, etc.? Well, the biggest lesson that Munger taught him was that time played a critical role in success. What Munger believed in is that pure intrinsic factors did catch up to price in the short run, but in the long run, having strong management, operations, and a brand made a big difference, and if you held on long enough, you would make a fortune.

What is long? Forever.

Holding assets and never selling—this is what Munger called 'sit on your ass' investing. To Buffett, this was completely foreign but he was open to the idea.

Their first opportunity with this style of investing came when See’s Candy was brought to them. In the book 'Snowball', Alice explains how See’s was a company known for its high quality, and they even had a name for it: 'See’s Quality'. When it was brought to Warren, he initially didn’t want to spend time on it because he understood the candy industry and knew how expensive companies were, so he passed it along to Munger for review. By the time they approached the owners, the company had a tentative deal on the table and were looking at a price of $30 million for assets worth $5 million. To Buffett, this was insanity. How can you pay a price that is 5x assets?

Munger told Buffett:

“See’s has a name that nobody can get near in California. We can get it at a reasonable price. It’s impossible to compete with that brand without spending all kinds of money”

Both Munger and Buffett decided that they would invest and hold given the lower downside on cash flows. They saw See’s like a bond with a 9% floor on cash flows, and continued by saying:

“We thought it had uncapped pricing power. See’s was selling candy for about the price of Russell Stover at the time, and the big question in my mind was, if you got another fifteen cents a pound, that was two and a half million dollars on top of four million dollars of earnings. So you really were buying something that perhaps could earn six and half or seven million dollars at the time”

Berkshire ended up buying See’s for $25 million with $4 million in earnings. This gave them a 9% return. Nothing great. That said, they believed their brand, management, and moat around quality would drive future growth if they 'sat on their ass', which they did. Over 50 years later, the investment blossomed and proved that Munger’s approach to long-term investing works, generating an 8,000% return on their investment (and it continues to grow to this day).

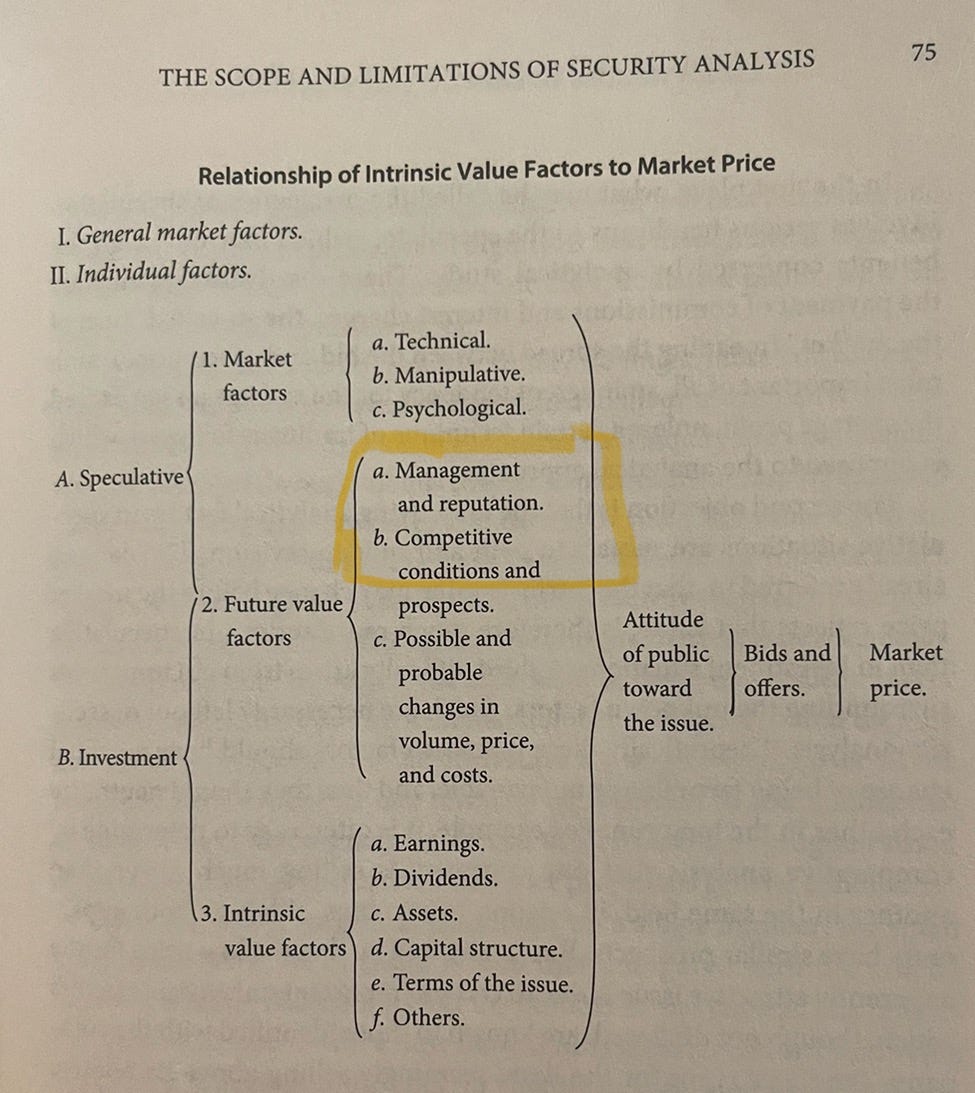

After their investment in See’s, Buffett believed in the power of the softer side of future value factors such as management, brands, competition, etc. (see chart above) and considered them as investments as opposed to speculations. That said, Munger and Buffett do rely on the foundational models for determining undervalued companies (based on the Graham approach) but made some exceptions when they considered the long term prospects of a business. The one thing that they all agree on is that market factors (momentum, technical analysis, etc.) should not be considered in the evaluation of great businesses.

From that day on, Buffett went from being a Graham disciple to a Munger disciple. Berkshire went on to invest in other great businesses at a fair price, including GEICO, Coca-Cola, Dairy Queen, American Express, Apple, and many more, turning Berkshire into a multinational conglomerate holding company that continues to generate ~25% annual returns on free cash, with ~$200 million of pure free cash flowing straight into their bank account weekly. Buffett’s job is to manage this cash on a weekly basis, with more than 60 CEOs reporting to him and his board. It's not an easy task, but a good problem to have.

Buffet may look like an old fogy to some people, but I can’t think of a better company with a better economic profile than Berkshire. No debt. All cash.

Now what is next for the investment world? We are starting to see a new group of value investors that consider (1) stronger growth potential, (2) market forces, (3) and even psychology that may impact the outcome of future value, which would go against the principles of Buffett and Munger. This is part 3.

Part 3 - Modern Day Investors

I will keep this section short. The reason why I had to explain the Buffett/Munger/Graham story in the previous section is that I felt I needed to provide some context as to how value investing evolved.

There is now a new school of value investors who align strongly with Buffett and Munger but take into consideration market cycles. This is the school of Seth Klarman (Baupost Group) and Howard Marks (Oaktree Capital Management). Seth Klarman believes in what he calls 'Margin of Safety,' which was applied based on the Graham philosophy, but he keeps his eye on the market and on institutional investors. He believes that most institutional funds are 'irrational' but yet manage significant amounts of money that tend to move markets. So it allows him to bet on companies that are not pursued by them. In his book 'Margin of Safety,' he goes on to say:

Investors must try to understand the institutional investment mentality for two reasons. First, institutions dominate financial market trading; investors who are ignorant of institutional behavior are likely to be periodically trampled. Second, ample investment opportunities may exist in the securities that are excluded from consideration by most institutional investors. Picking through the crumbs left by the investment elephants can be rewarding.

Investing without understanding the behavior of institutional investors is like driving in a foreign land without a map. You may eventually get where you are going, but the trip will certainly take longer, and you risk getting lost along the way.

- Seth Klarman

So in this case, he applies the deep value philosophy and tracks swings in the market to find those who act ‘delusional’.

According to Wikipedia, since his fund's $27 million-dollar inception in 1982, he has realized a 20% compounded return on investment. He manages $30 billion in assets today. His model clearly works with a slight tweak on Buffett’s model.

Howard Marks has a similar philosophy but goes deeper into investor psychology and how they impact market movements.

If you are interested in these market dynamics and how they relate to value investing, I recommend two of their books:

If we go back to Graham’s chart, they would consider the highlighted factors as part of the investment process (as opposed to speculation):

Now that we are done with these guys, what’s next from here?

I am an early stage investor (and entrepreneur), and part of being in the early stage is to envision what the future looks like. This would be a sin for value investors since most value investors invest in companies that have some proven history, with less weight on future prediction.

That said, having this 'value lens' is important when you picture what your company can become later on, whether as an investor or an entrepreneur. You always have to ask yourself, 'In 5, 10, 15 or 20 (or beyond) years, how much will my company be worth? How would Buffett, Marks, and Klarman see it?' The answers to these questions become easier the simpler your business. Answering this question for an AI company or an ecommerce company is much harder than for a fast-growing brick-and-mortar business, for example.

This reminds me of the conversation Bernard Arnault had with Steve Jobs that was mentioned previously:

Source: Yahoo News

As an early-stage company, you have hardly any revenues or cash flows, and what brings value to the eyes of early-stage investors are answers to the following questions:

How likely is it for you to achieve cash flows?

How long will it take to achieve a level where you have proven cash flows?

How would the market react to these developments as your company evolves to that more mature state?

Number 1 is critical because the stronger the likelihood of achieving cash flows, the lower the discount rate you can apply to the future value, resulting in a higher valuation.

Number 2 is equally important because the sooner you achieve the 'realistic' outcome, the higher the value of your company (from a time value of money perspective).

Number 3 then would allow investors to understand what smart investors in the market would pay for your company at mature states.

There are times when companies have very little revenue and cash, but investors have such strong conviction of the future outcome that they end up paying ridiculous prices for the company.

If you want to learn more about this, here is a good article by Andreessen Horowitz about how they justify high entry multiples: [link to the article]. If you read this article, you will realize that even an early-stage deep tech fund like Andreessen Horowitz applies the later-stage principles when looking at entry multiples.

So is Benjamin Graham useless in today’s world? No, he is not. His principles are timeless and work as well as they did in 1934, but applied differently and under a new environment where information is much more readily available and business disruptions are much greater.

Just as in golf, the swing is always different, courses transform, and golf clubs improve. Yet despite these shifts, golfers recognize the importance of fundamental lessons and habits: the art of a good grip and the stability of a strong stance. These timeless principles not only anchor our game but also serve as a guiding force towards mastery, reminding us that while the game may change, the foundations remain and will always remain for the foreseeable future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company based in the Philippines that partners with entrepreneurs across a wide range of industries. He is the Co-Founder and Director of The Independent Investor.