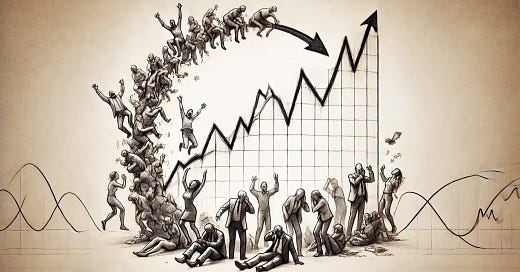

Sketch from DALL-E

In the book Crossing the Chasm by Goeffrey Moore, he talks about taking early stage products to the mainstream, and what it means to pass this critical stage between invention and adoption. This is what he calls the chasm. Most startups develop products only to see it adopted by a handful of technical nerds, failing to cross over to the entire market (think of your barber or local laundromat owner).

He discusses how companies can break away from early adopters (the visionaries and nerds) to enter the mainstream (early and late majority) to generate outsized returns. Think of Apple (iPhone), Microsoft (Microsoft Office), and Amazon as examples. Everyone uses them, not just a handful of nerds and visionaries, and that’s what makes them valuable.

I am writing about a different chasm. It relates somewhat to the chasm that Moore writes about, but it focuses on a more boring, but yet critical, aspect of taking your company to the next stage of growth.

This is cash.

When starting a company, your first task is to find product-market fit. The second is to ensure it sustains itself over the long haul, and that happens when you cross Moore’s chasm. If you’re confident it will reach—or has reached—the ‘other side,’ then you have achieved true product-market fit.

Now that you’re on the revenue train, the next concern becomes, as a seasoned investor once told me, making sure 'the wheels don’t fall off.' I like this analogy because it fits the unpredictable ride of startups.

What does this mean?

As revenues grow, there is a need to meet demand, and most of the time for early stage companies, demand can be so strong—even exponential—that it outpaces operational capacity. This means you need to invest and spend ahead of revenues to prepare for growth. This is where many startups struggle, which is why we often see startups 'losing money.' It’s the burn to justify the ends (eventual sustainability).

How do you balance this growth with profitability as you scale? Making sure you know when the period of stability begins, where the net cash return from revenues allows a company to sustain itself without further investor money. Achieving this requires regular budget planning and cash flow assessment. Missing this can derail any company, even the best ones with the best products.

What I found useful is to have a regular weekly cash management call with all finance team members, and to constantly project and adjust based on current levels of cash. As we all know from history, actuals never align with projections, for better or worse. As Howard Marks says:

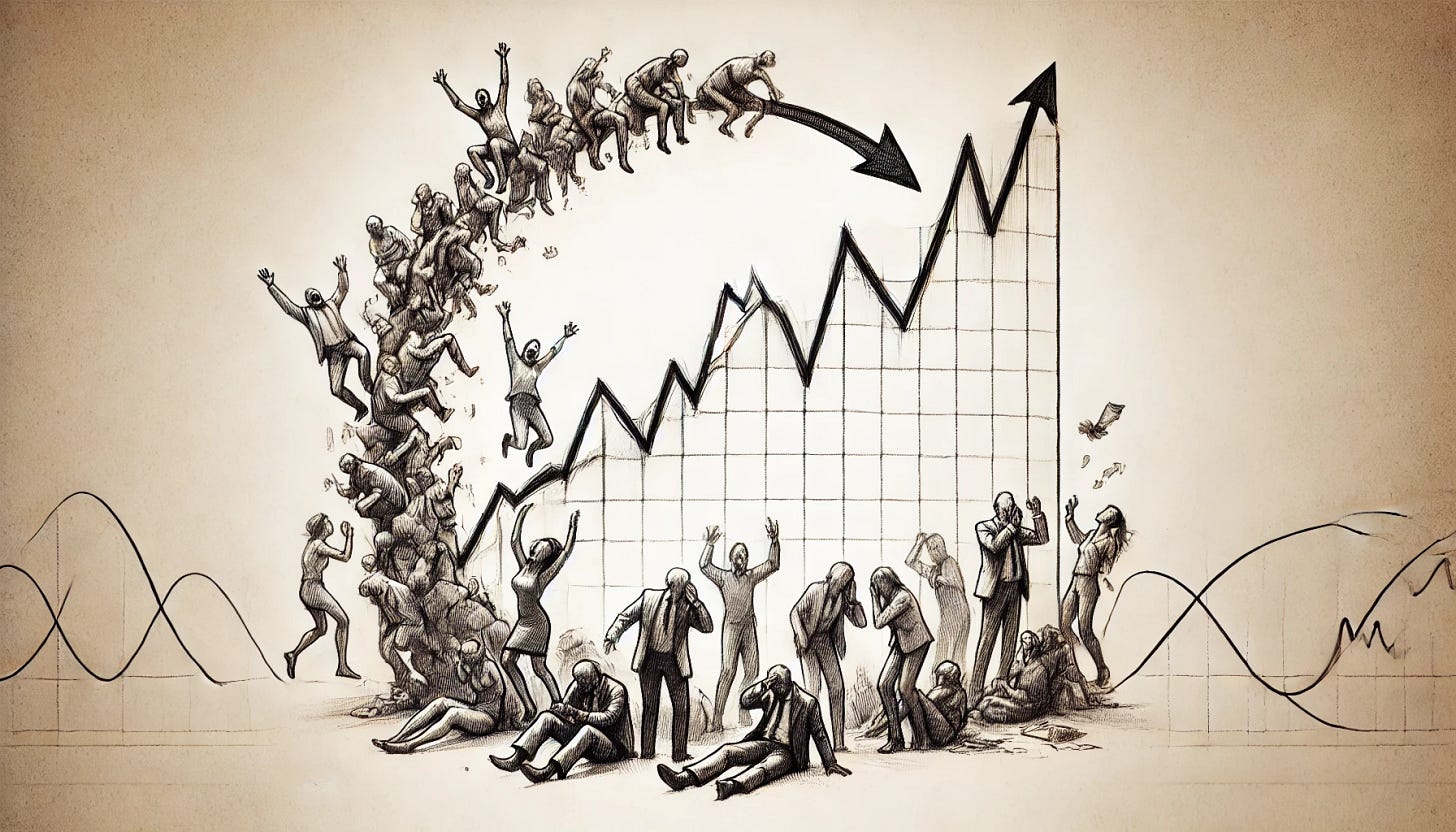

Rule number one: most things will prove to be cyclical.

Rule number two: some of the greatest opportunities for gain and loss come when other people forget rule number one.

The main reason for the cyclicality in our world is the involvement of humans. Mechanical things can go in a straight line. Time moves ahead continuously. So can a machine when it’s adequately powered. But processes in fields like history and economics involve people, and when people are involved, the results are variable and cyclical.

The main reason for this, I think, is that people are emotional and inconsistent, not steady and clinical.

Quote from The Most Important Thing

Bottom line: Businesses are run by people and people are emotional and inconsistent by nature. This means founders have to work harder to build a system to track the ebbs and flows of the business, and how that affects cash.

Having weekly cash management calls allows you do be nimble enough to adjust as you grow to meet certain thresholds in the future. What you don’t want is a situation where you constantly invest, invest and invest, and you later realize that the wheels have fallen off. When you reach the point where cash returns can’t recover to meet operational demands, that’s when companies fail. As Tony Hsieh (Founder of Zappos) once said, “there are two reasons companies fail, either they run out of cash or the founder gives up.” A founder can keep fighting but without cash, there is only so much you can do.

One story is Jawbone. They were once a leader in Bluetooth headsets and fitness trackers and raised over $900 million from Silicon Valley’s top VCs. They hit a valuation of over $3 billion. Despite strong early revenue from wearable tech, they couldn’t handle competition from companies like Fitbit and Apple. Jawbone’s aggressive R&D spending and marketing costs burned through cash faster than revenue could replenish it, and production issues further hurt their cash flow. This led to their closure in 2017.

Then you have successful ones like WhatsApp, where in 2011 Sequoia Capital made an investment of $8 million. WhatsApp experienced exponential growth. By 2013, the platform had more than 200 million active users and a team of only 50 employees. Sequoia kept investing with an additional $50 million during this period, valuing WhatsApp at $1.5 billion. On February 19, 2014, Facebook announced its acquisition of WhatsApp for $19 billion, marking the largest venture-capital-backed acquisition at that time. Sequoia invested a total of $60m and when they exited to Facebook, it was worth $3.5b, a total return of ~50x their money in 3 years.

In contrast, there’s Mailchimp, which grew more conservatively and self funded itself with customer revenue for over 20 years. They prioritized cash flow and let growth follow naturally—a slower but ultimately more reliable route. Eventually the founders sold their company for $12 billion. Was it worth it for them to wait for 20 years to hit that $12b net worth? It depends on who you ask.

In between the extremes lie those who rely on outside capital yet are determined to achieve lasting sustainability. They aim to be aggressive where it counts while being frugal and resilient at the same time. As John Maynard Keynes once said, ‘In the long run, we are all dead.’ And while it’s enticing to dream of success stories like WhatsApp’s, reality often looks different. Wealth, more often than not, is built slowly over time, requiring a blend of patience and adaptability. I prefer to think in the long term, but I’m not sure waiting indefinitely is for me (but dreaming of legacy assets is enticing). I lean toward having the options for exits and dividends—not as obligations. It’s about striking the right balance between long-term growth and immediate returns.

Despite the glory we see in Silicon Valley, with all the big fundraises and media glitz, behind every success are lessons in cash management. These lessons are subtle and less glamorous, and they relate to building a culture of frugality as you scale. This is why frugality is one of the most important virtues for any founding team, and you can see it reflected in the clothes founders wear, the watches they use, the cars they drive, where they eat, and what they talk about. People make fun of me for it, but in reality, these are some of the biggest factors behind successful founders.

If you raise money, it should be used to drive revenue, not to fill your pockets. This requires extreme frugality at the founder level. Wealth should be directed toward building equity value, not immediate cash in your pocket.

Paul Graham relayed this in his article How to Start a Startup:

The other reason to spend money slowly is to encourage a culture of cheapness. That's something Yahoo did understand. David Filo's title was "Chief Yahoo," but he was proud that his unofficial title was "Cheap Yahoo." Soon after we arrived at Yahoo, we got an email from Filo, who had been crawling around our directory hierarchy, asking if it was really necessary to store so much of our data on expensive RAID drives. I was impressed by that. Yahoo's market cap then was already in the billions, and they were still worrying about wasting a few gigs of disk space.

When you get a couple million dollars from a VC firm, you tend to feel rich. It's important to realize you're not. A rich company is one with large revenues. This money isn't revenue. It's money investors have given you in the hope you'll be able to generate revenues. So despite those millions in the bank, you're still poor.

For most startups the model should be grad student, not law firm. Aim for cool and cheap, not expensive and impressive. For us the test of whether a startup understood this was whether they had Aeron chairs. The Aeron came out during the Bubble and was very popular with startups. Especially the type, all too common then, that was like a bunch of kids playing house with money supplied by VCs. We had office chairs so cheap that the arms all fell off. This was slightly embarrassing at the time, but in retrospect the grad-studenty atmosphere of our office was another of those things we did right without knowing it.

Here is another video of Eric Schmidt talking about his experience with Google in the early days:

I remember when we started our bread business, we thought a second round of funding might mean a real office for the team. In fact, we took frugality into account. Reality? It’s even more stripped down than we’d imagined. We’ve got a small conference room, right in the heart of our busy commissary. It’s our 'war room,' and as we grow, it’s only going to get tighter. I figured there’d be a budget for eating out with stakeholders after our second funding round, but we’re still holding meetings at home. We’re cash-poor, but it’s a choice we’ve made to build a lasting business. No fancy cars, no nice watches, no designer clothes could replace that kind of value.

Returning to our weekly cash management discussions: as companies scale, they should constantly ask themselves, 'What can we give up operationally without sacrificing growth momentum?' In other words, how can we keep growing at our ideal pace (or better) with the lowest possible spend? So, despite having cash in the bank from investors, companies should aim to reduce spending to hit that optimal number that sustains growth. Why? Because they need cash for later just as much as they need it now.

Then sometimes you hit a paradox. New opportunities begin to emerge for the business, relating to both growth and efficiency. One path is for a new product line that you are confident will do well which you did not predict earlier, and another path is to invest in technology to increase efficiency. These were unforeseen when you initially prepared your budget during the last fundraise. However, you can only capitalize on these if you have extra cash to invest upfront today.

These are tough choices, and this is when you must ask yourself, 'Is it worth giving up equity or raising debt to pursue these opportunities?' Here, you compare potential growth (from expansion) or savings (from efficiencies) with the cost of capital, keeping in mind that not all equity and debt are created equal. As you grow, new opportunities will arise—some will be distractions, and some will be justified. it’s important to have a strong strategy and finance team to assess all options and decide on the best funding approach, all while maintaining focus on your core product. This dynamic never ends.

As you navigate the cash chasm, think not for yourself but for the company. Aim to strike the right balance between growth and cash, ensuring the wheels don’t fall off along the way. When founders say they’re 'poor,' this is what they mean. Startup life isn’t what convention suggests—high-flying IPOs, fancy cars, and VIP parties. That comes years later, perhaps at an exit or a financial milestone. But 99% of the time, you’re in the trenches building something that will last a lifetime. Something that is not often understood by most.

In the end, the journey of building a startup that endures is far from the glossy image often portrayed by the media. Real value isn't in the flash of big exits that may come years later; it’s in the daily grind of making disciplined choices, in the huddle of weekly cash flow discussions, and in the commitment to stay lean while maximizing every dollar’s potential. The truth is, founders need to think like 'poor' and hungry entrepreneurs, understanding that real wealth is held through equity in the company.

In the words of Howard Marks, remember that 'most things will prove to be cyclical,' and as a founder, your job is to ensure that when the cycle comes full circle, your wheels are still firmly on the ground.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company that invests in and builds high-growth, early-stage businesses that serve the underserved Philippine mass market. He is also the Co-Founder of The Independent Investor, a media platform spotlighting early-stage companies and innovation within the Philippine startup ecosystem.