Source

Some people have an impressive ability to turn idea after idea into thriving businesses. It’s a rare pattern, but when it appears the results are nothing short of inspiring—success builds upon success. While this may not be true for everyone, I’ve noticed an interesting trend over the years: certain individuals have a unique talent for taking their ideas and transforming them into successful enterprises time and time again.

While some struggle repeatedly without achieving significant success, others seem to have a knack for developing new companies. Occasionally, individuals may build a single successful venture but fail to progress further. This raises a question I’ve been asking myself over the years: What sets apart those who achieve ongoing success from those who do not?

It seems that their success is created by a kind of 'luck'—not in the literal sense, but in a figurative and productive sense. This 'luck' favors those who persistently pursue a clear mission that addresses large problems. This initial stroke of luck can lead to success that often breeds further success. How long this lasts depends on the industry they are in and the strength of the tailwinds within that sector. Similar to how champions in sports continue to achieve more after their initial victory, successful entrepreneurs often build on their early success until the tailwinds eventually die down. In business, we see similar patterns of sustained success.

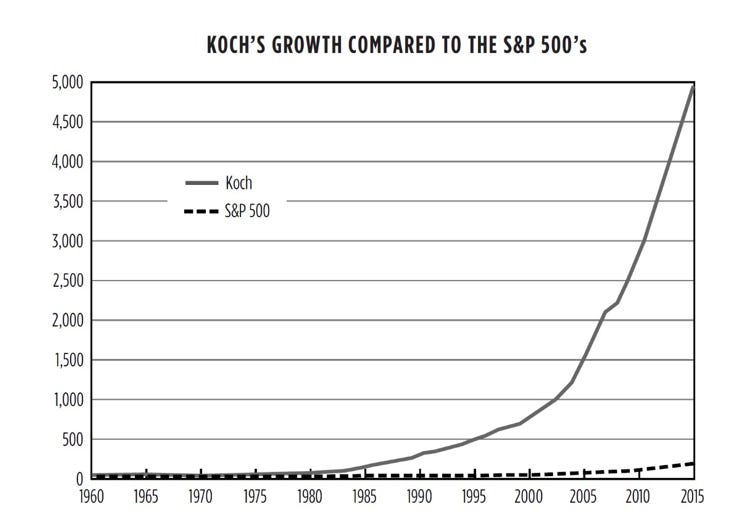

I was re-reading Charles Koch’s book Good Profit earlier this week, which is basically his autobiography tied to his business philosophy, and he mentioned something interesting about how Koch Industries develops its businesses. It caught my attention because his track record speaks for itself—having grown $21 million in 1961 into roughly $150 billion today.

He goes on to say:

“I often think of what we do as bricklaying. Or perhaps more precisely, stonemasonry. Once a stone has been carefully selected and set, it shapes a new space in which the mason can set yet another well-chosen one. Each stone is different, but they all fit together to create a framework that is mutually reinforcing”

This struck me as gold, as it answers a question I’ve always had: why does initial success often lead to future success in business? The answer lies in what Charles Koch calls a capabilities-driven business model. When Charles Koch and Sterling Varner took over the business from his father, they began with crude oil gathering, eventually applying their insights to crude oil trading. From there, they seized new opportunities in gas liquids gathering, fractionating, and trading other commodities. This led them to forward integration into areas like nitrogen fertilizers. Oil refining became the foundation for an entirely new chemicals business, focused on polymers, fibers, and pulp and paper, which ultimately brought them downstream to consumer products on grocery shelves.

This idea of a capabilities-driven business model (let’s call it the CD Business Model) runs counter to what most venture capitalists or private equity firms support—a strict focus on specific, proven paths. The CD Business Model is more long-term, as many of its payoffs are not immediate or certain. What it advocates is the consistent testing of new ideas, with core businesses providing support. This approach runs opposite to the grand plans most companies pursue. The CD Business Model assumes humility, acknowledging that while you can’t predict the future, you have core capabilities that allow you to explore new frontiers, wherever they may lead.

“It's not whether you're right or wrong, but how much money you make when you're right and how much you lose when you're wrong.”

George Soros

Your core business is a single node, and the CD Business Model can be thought of as developing low-cost call options for companies to establish new nodes. You can test many ideas—most will fail—but the downsides shouldn't be severe enough to impact your overall business or distract from your core focus. Over time, you’ll discover gems that generate outsized returns, which then become new nodes, opening up more opportunities for forward integration.

Peter Thiel discusses something interesting about vertical integration in the following video:

When referring to some of the previous successful companies, he goes on to say:

“This is actually done surprisingly little today and this is a business form that is very valuable. We live in a culture that is very hard to get people to buy into anything that takes long to build. The key to these companies was the vertically integrated monopoly structure they had. “

Thiel is very similar to Koch in this sense.

This brings us back to the debate of specialization versus generalization. Many executives often criticize generalization, misunderstanding its true nature. I would argue that these high-performing builders are not generalists, but instead are specialists in the capabilities-driven business model focused on investing, building, and forward integration. Some may wonder how one person can manage so many ventures and succeed at each. It doesn’t mean they are jumping between companies like headless chickens. Rather, they’ve mastered the art of human leverage—empowering others to execute tasks while establishing a governance structure that ensures success.

It might sound strange, but aside from the ethical choices and target industries, there are a few differences between how Berkshire Hathaway, Koch Industries, and the Mafia run their businesses. They are largely non-bureaucratic, highly decentralized, with small head office teams, and operate with diverse holdings—relying heavily on the power of human leverage.

In other words, they are masters at empowering other people to create value for them.

Mafia Corporate Structure

Source

As your company grows, you have to ask yourself: what is the next best use of cash? Every expansion opportunity comes with opportunity costs. Some offer immediate returns, while others may take longer but yield larger payoffs (bricklaying). You have to constantly weigh whether it's time to lay bricks or pursue more immediate opportunities. I believe the key to building an empire is striking the right balance between shorter-term, more certain priorities and longer-term, less certain opportunities.

I find it most useful to assign probabilities to outcomes and apply them to IRR (Internal Rate of Return) and NPV (Net Present Value) results. These probabilities are based on the likelihood of success for each project (a very subjective exercise). When deciding on a project, these probability-weighted metrics are compared against each other. Longer-term, more experimental projects often have a higher failure rate but offer significantly larger potential value (fat-tail outcomes), while more immediate and consensus driven projects tend to provide lower, more predictable returns (normal distribution). Generating alpha typically requires greater investment in the longer-term experiments. Another method I like using is the equity bond method, where you first arrive at your own personal required return on equity, and then back-solve the ideal value.

Entrepreneurs have to remember that the CD Business Model demands a degree of corporate frugality, which may involve sacrificing dividends or other forms of cash payouts for shareholders—a challenge that many find difficult to accept.

As you prepare to take the next leap for your business, you'll receive advice from many different sources, often emphasizing the need to focus. When you hear this, challenge them to clarify what 'focus' truly means. Focus is relative to the kind of value you aim to achieve for your business—whether it's achieving immediate, specific goals or pursuing a strategic, long-term vision. Understanding this difference can help you align your efforts with your broader objectives and drive meaningful progress.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company based in the Philippines that partners with entrepreneurs across a wide range of industries. He is the Co-Founder and Director of The Independent Investor and Co-Founder of Cocopan.