Accepting Equity

Understanding the balance between dilution and growth

There comes a time in a business’s life when it must seek capital to grow. Usually during expansion mode, companies face a liquidity crunch. Meaning, and assuming that the business is doing well enough, demand starts outstripping its ability to supply.

This is a good problem to have. Yet one of the most dangerous situations for any business is stretching beyond its limits to meet demand.

Meaning, you offer something of value, and a customer agrees and offers the exchange, but you renege on your promise. Losing a sale is always worse than being over prepared for one.

So how can a startup or business prepare for that moment? They must be ready and stocked at all times, which can mean fronting capital early on to meet future demand. This is what businesses call “cash burn” and why startups and early-stage companies can remain unprofitable for some time. Of course, there are those rare companies that can spit out products with no marginal cost to meet rising demand (think Microsoft in its early days), but such cases are rare. Even in today’s tech driven world, burn usually comes from talent whose costs are rising to never-before-seen levels.

So what does a company do once it reaches this inflection point?

It has two options: debt or equity (or both). There are hybrids, like convertible notes, but we’ll leave those out for simplicity’s sake.

Debt is pretty straightforward. You borrow money from someone. That person sets fixed terms for interest and principal repayment. You know exactly how much you’ll pay in interest each month, and the principal must be repaid after a set period. As a growing company, your risk is high and the ability to pay is low. Debt is a binding obligation, and at this stage it rarely works out in your favor. Fixed obligations limit the flexibility you need as you scale. And as an early-stage business with risks lurking, the one thing you need is flexibility. Trust me here.

Equity on the other hand is a bit different. It is not an obligation and instead it is ownership. There are no fixed terms. No interest. But in exchange for money, the investor gets ownership in your company. What’s important here is to understand your company valuation in order to exchange a fair ownership percentage of your company for the amount of money that is being offered.

What I often encounter are situations where founders either give up too much or not understand what it means to give up ownership. It’s simple. It means someone gives you cash, and in return for the risk he is taking to join your company, he has the same rights (or limited depending on the type of equity) as you, the owner.

The next question is how much to give up. This is where valuation is important. It is very easy to raise capital from someone if you have a decent business. Anyone can do it. But it’s not that straightforward to raise the right capital at the right price (share of your business). As a founder, you don’t want to give up too much or else you lose control and incentive in running the business.

Let’s step back for a bit. Before we even raise equity, we should be asking ourselves why we are doing it in the first place? The answer should either be because (1) I need money to expand operations and/or (2) the opportunity cost is too high not to. Opportunity cost is interesting because the mindset is that if you continue investing and growing, the firm’s value increases and so does the value of the company. In that sense, opportunity cost is exactly what you’re after. But let’s not forget the most important part: it’s all about opportunity cost net of dilution.

When you raise equity as a founder, you give up ownership (dilution).

Here is a hypothetical question:

Would you rather own 10% of something worth $1 trillion or 100% of something worth $20 billion?

It’s clear which one gives more value. Sure, you might lose control of the business, but your net worth is 5x that if you were to own 100%. Jeff Bezos owns 8.29% of Amazon and is worth $236 billion, while Mark Zuckerberg owns 13.5% of Meta is worth $262 billion. You get the picture. For a fast growing company addressing a big market, if you are after capturing net worth, it is better to own less in exchange for growth, than it is to own more while sacrificing growth.

“I’d rather earn 1% off 100 people’s efforts than 100% of my own.”

- John D. Rockefeller Sr.

So what is that threshold? High growth to me could mean something different to you.

I like to think of it this way. For every dollar in, you as a founder need to know where that specific dollar takes you 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 years from now. Taking $1 million today will yield very different results from taking $1 billion today (assuming your business can even utilize that amount). Not only that, as a founder you have to make sure that whatever dollar is taken is put to good use. You don’t want to take an amount that is short of your goal, but you don’t want to abuse it either (think WeWork).

Understanding this dynamic is where finance and capital budgeting come into play. It involves knowing how to measure your revenues, gross profits, operating profits, and all the way down to Net Income After Taxes (NIAT). Once a founder masters this, they can project into the future (using conservative assumptions) how every dollar can add value to the organization. And once that future value is clear, it can be brought back to the present using conservative discount rates that reflect its true risk.

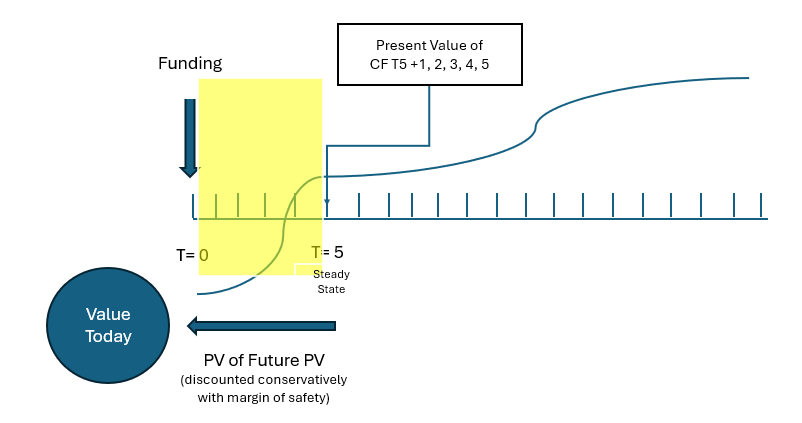

It looks something like this:

It’s about understanding where your money takes you, and what your steady state looks like at that future point in time (T-=5), then bringing that back to the present (T=0) to understand your range of values. I know this sounds strange and most textbooks (and schools) teach DCF as a static equation (I have yet to find one that talks about taking the present value of a future present value), but in the high growth world, it is the opposite of static. Your business is not a powerplant, or a mall, or a widget manufacturer. It is a high burn machine with exponential demand and extreme risk. If you look at the graph above, the yellow area indicates the high-risk high-growth phase where cash is utilized up to the steady state.

Steady state is into the future, so conservatism must play a role in discounting to the present.

So, if your current price reflects a valuation where you give up too much, then your growth rates don’t justify the capital that is being offered. You are less likely to accept equity. You may want to negotiate the amount raised to lessen the equity until some future point in time when you think you can hit that growth curve. So it is about managing expectations and understand your value today before taking the money.

Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator, has a good formula that is more back of the envelope.

He uses: 1 / (1 - N)

So here, if I offer you $1 million for say 10% of the company, then you have to hit 11% growth in order for you to be break even ( 1 / 1 - 0.1). Anything more makes you net ahead.

Paul Graham in his essay The Equity Equation, says:

“For example, if an investor wants to buy half your company, how much does that investment have to improve your average outcome for you to break even? Obviously it has to double: if you trade half your company for something that more than doubles the company's average outcome, you're net ahead. You have half as big a share of something worth more than twice as much.”

That’s a simple way to put it. But to understand whether you can grow by that much, you still have to plug in the numbers and project them.

I am not claiming that these are the only ways to accept equity. I am also looking at this purely from a numbers perspective. There are also other softer sides of the equation that founders need to look out for, such as investor philosophy and alignment. You don’t want a dud sitting on your board. At the very least, you want someone who can add value beyond the numbers.

The next time you think of accepting equity, go back to your budget and projections, and work out something that is fair given your growth trajectory. Building trust, and offering something of value to investors will always earn you credits for the future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company that invests in and builds high-growth, early-stage businesses that serve the underserved Philippine mass market.