Every other day, my daughter asks me to read her parts of Aesop’s fables, and I found one that resonated with me—the story of the Ant and the Grasshopper:

In a field one summer's day a Grasshopper was hopping about, chirping and singing to its heart's content. An Ant passed by, bearing along with great toil an ear of corn he was taking to the nest.

"Why not come and chat with me," said the Grasshopper, "instead of toiling and moiling in that way?"

"I am helping to lay up food for the winter," said the Ant, "and recommend you to do the same."

"Why bother about winter?" said the Grasshopper; we have got plenty of food at present." But the Ant went on its way and continued its toil.

When the winter came the Grasshopper found itself dying of hunger, while it saw the ants distributing, every day, corn and grain from the stores they had collected in the summer.

Then the Grasshopper knew...

It is best to prepare for the days of necessity.

The lesson here is clear.

Preparing for the days of winter applies to many aspects of life. A big part of this involves understanding risk and how preparation and awareness enable resilience during difficult times. Those who take the time to prepare are the ones who prosper over the long run.

The idea of risk is interesting. If you ask any investor how to define it, you will likely get different answers. What is risk? How do we measure it? We each have our own views on the matter, but one thing is certain: we all engage with risk in our daily lives. Otherwise, we wouldn’t invest, start companies, pursue projects, or build careers.

For example, when considering a career, there is always an assessment of risk and return. You first evaluate the likelihood of monetary success (earnings) alongside your level of interest (passion), and then combine that with an assessment of potential downside (e.g., 'If I graduate with this degree, can I land a good job? If I lose a job, can I bounce back or maybe even start a company?'). As a student, you begin comparing options and try to determine which path offers the highest expected value with minimal opportunity cost.

These are normal factors to consider when choosing a career, and there is no single, quantifiable formula to guide this decision. If such a formula existed, everyone would be happy and rich. As we all know this is not the case, because path selection in your early career is a subjective process with many variables that you might not foresee along the way.

This way of thinking also applies to investing and venture building. When someone starts a company, they usually try to understand the potential upside relative to the downside. How much can I gain given the level of downside risk if I start this company? Investors ask similar questions: If I invest in this company, how do I know the risk justifies the returns? How much value am I getting relative to other investments?

But what is risk?

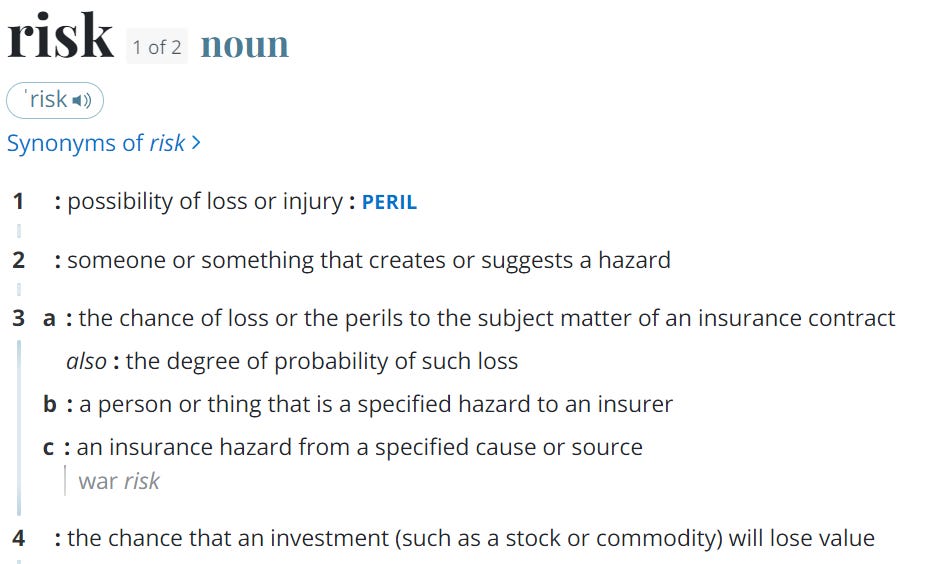

This is what Merriam-Webster has to say:

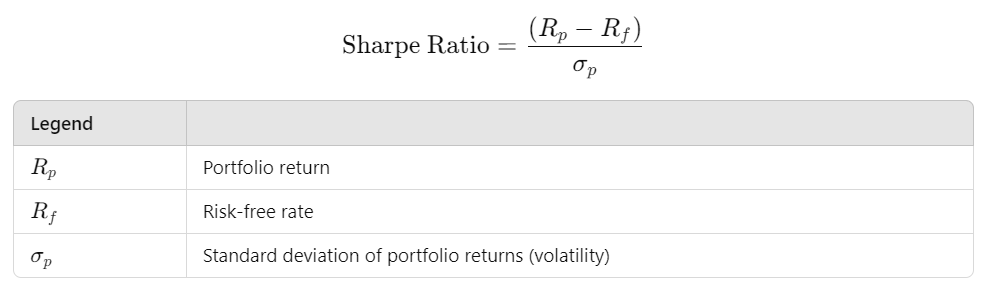

The definition is clear: it’s the possibility of loss, it is the chance that an investment will lose value. Depending on whom you ask amongst the investment community, you might get a different answer. Most universities and even institutional investors equate risk with volatility, which means that if something is volatile (unstable), there is a chance that it might lost value or result in complete loss. I’m not exactly sure why they chose volatility as a measure of risk, but I suspect it’s because volatility is measurable. If something isn’t measurable, it becomes hard to prove, so it does not fit into any formulas. For example, the Sharpe Ratio, proposed by Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe, is defined as follows:

The idea is that the higher this ratio, the better the risk-return profile of an investment. The concept makes sense, as it allows investors to measure the historical performance of a public asset (private assets lack regular price history) and assess how volatile it is under certain scenarios.

But is that really the case? Are all unstable investments risky? Or, put another way, are all stable investments safe? This is where a big divide exists between different schools of thought.

Going back to the fable of the Grasshopper and the Ant, the Grasshopper was hopping, chirping, and dancing under the bright sun, while the poor Ant toiled away. What the Grasshopper didn’t realize was that sunny days don’t last forever, and assuming you can relax under rosy circumstances is a fool’s game. This is what the Ant understood despite the Grasshopper's temptations. The same applies to investments. Just because something has been safe for a long time (low volatility) doesn’t mean it will stay safe forever. Look at the Great Financial Crisis, the Asian Financial Crisis, and the lead-up to the Dotcom bubble. In the lead up to each of these crises, volatility was low and market confidence was at its peak.

Great investors sacrifice during good times and deploy during bad. The saying 'Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful' holds true.

So if volatility doesn’t accurately reflect risk, what does? At the end of the day, what matters is whether you (1) preserve your money (avoid loss) or (2) achieve a return that remains permanently above your loss threshold. Let’s refer to the odds of not achieving this as the probability of loss (PLoss) for simplicity. When considering these two factors, everyone will have their own views on the probabilities based on their level of confidence in the outcome.

The next question is, 'Why don’t we have a formula that reflects PLoss?' This is a difficult question to answer because PLoss is an extremely hard number to measure or quantify. Past success is no indicator of future success as we have learned from history, and the same goes for past loss. As a result, using PLoss in the denominator (instead of volatility) would be extremely challenging, because it is impossible to prove the probability of loss mathematically. Analysts can present various outcomes based on different assumptions and scenarios, but the probability of loss will still vary from person to person. In contrast, volatility is easily measurable and defendable based on historical data (i.e. VIX).

So where does this leave us?

This doesn’t mean we can’t use our own probability of loss. The difference is that it’s a subjective exercise. One person's view of the risk of permanent loss will differ from another's. Even if two people arrive at the same PLoss, one might be more confident about the upside than the other.

This is why investing is more an art than it is a science despite what universities teach.

Returning to PLoss, I’ve developed a formula that I use which could be helpful for any early-stage investor (hopefully). However, I guarantee that the results will vary depending on who you ask.

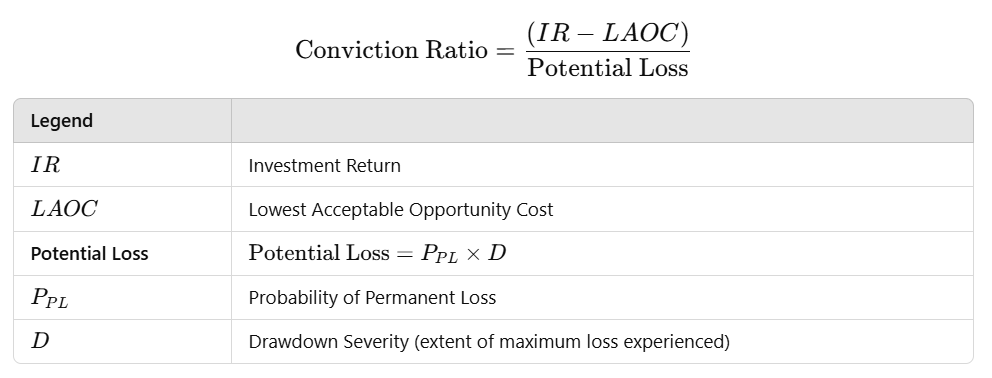

Let’s call this the Conviction Ratio:

I have replaced the risk-free rate with the lowest acceptable opportunity cost (LAOC), reflecting an investor’s personal risk level. Let’s be real—when we evaluate opportunities, not everyone thinks of government bonds as the only next safe option, especially for private market investors in emerging markets. There are other assets besides AAA-rated government bonds that can be viewed as 'risk-free,' and this is based on personal risk tolerance. In other words, this rate represents our lowest return threshold, aligned with our minimum acceptable risk. It could be higher or lower than the typical risk-free rate. For the denominator, I have replaced standard deviation with potential loss, defined as the product of the probability of permanent loss and drawdown severity (the extent of maximum loss experienced). I hope I don’t insult any William Sharpe fans here but I am doing this for the sake of practicality and realism.

The same rule applies as with the Sharpe Ratio: the higher this ratio, the better. This allows any investor or entrepreneur to evaluate opportunities and ask, 'Does this project or investment offer higher returns than what is currently available to me at a certain level of risk? What is the likelihood that I will permanently lose my capital compared to the next best option?'

These are simple questions but extremely important.

As Howard Marks says in The Most Important Thing:

Return alone — and especially return over short periods of time — says very little about the quality of investment decisions. Return has to be evaluated relative to the amount of risk taken to achieve it. And yet, risk cannot be measured. Certainly it cannot be gauged on the basis of what “everybody” says at a moment in time…

The reality of risk is much less simple and straightforward than perception. People vastly overestimate their ability to recognize risk and under-estimate what it takes to avoid it; thus, they accept risk unknowingly and in so doing contribute to its creation. That’s why it’s essential to apply uncommon, second-level thinking to the subject.

A broad consensus that something’s too hot to handle is almost always wrong. Usually it’s the opposite that’s true.

Risk means uncertainty about which outcome will occur and about the possibility of loss when the unfavorable ones do.

Ultimately, there’s no single formula that captures the true nature of risk because, at its core, risk is subjective. It’s shaped by your own experience, judgment, and willingness to challenge the consensus. PLoss can guide you, but it’s still just an approximation.

The real edge comes from being able to spot potential risk where conventional wisdom falls short. Just like the Ant, it’s about being prepared for what others might ignore, knowing that good times don’t last forever. This doesn’t mean hoarding resources; it means understanding when to take risks and when to be cautious, even if everyone else is doing the opposite.

So next time you’re faced with a decision, whether it’s an investment or a new venture, don’t just ask yourself, 'What are the returns?' Instead, ask, 'What am I missing? Where are the hidden risks, and how do they change the outcome?' The more you can think in terms of scenarios and possibilities, the better you’ll be at navigating the uncertainties. And in the end, it’s not about having the perfect formula—it’s about having the right approach.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keenan Ugarte is Managing Partner at DayOne Capital Ventures, an independent private holding company that invests in and builds high-growth, early-stage businesses that serve the underserved Philippine mass market. He is also the Co-Founder of The Independent Investor, a media platform spotlighting early-stage companies and innovation within the Philippine startup ecosystem.